Are you the perfect musician? No? Well, that makes two of us who aren’t!

I’ve written on the Score Lines blog before about our need for perfection. We all know, deep down, that perfection may be a laudable aim, but in reality we rarely achieve it. I see this in my own working life, both in my playing and the mistakes I hear from other musicians. We all make excuses and apologies for our errors and there are certain phrases I hear time and again - from my own mouth and those of others. Teaching my evening class a few months back I heard familiar exclamations: “Oops, I missed the key signature”, “I forgot my reading glasses” and many more. It occurred to me that pulling these musicians’ excuses together might be an interesting and entertaining project, so I called out to my Score Lines community for your help.

Boy, did you come up with the goods! Over the last couple of months my email inbox has been peppered with wonderful emails from recorder players around the globe, confessing their mistakes and the ways they try to excuse them. Many a time I’ve found myself nodding in recognition and chuckling out loud. It’s time to bring your words to the wider recorder world so we can all be reassured these mistakes are completely normal. A huge thank you to everyone who got in touch to pass on their excuses - be that via email or in person. All your confessions will perpetually remain anonymous - it’s only my own deficiencies I’m openly revealing below!

Looking through your messages, our musical excuses tend to fall into various categories, so I’ve grouped them accordingly here. I’m going to talk about my own failings, bringing in lots of your comments along the way. Yes, professional musicians make mistakes too. You may not always notice them, and that’s because we’ve learnt through painful experience how to cover them up well! You’ll hear about some of my embarrassing moments and I hope perhaps my confessions may be reassuring.

Let’s dive in and explore the treasure trove of musical excuses we’ve gathered together between us…

Notational niceties

We all know we should look at the start of our music before we begin playing - the clef, key signature and time signature are useful pieces of information aren’t they? Can you say, hand on heart, that you always do this? No, me neither! If I had a pound for every time I had to make a swift, panic stricken glance back at the beginning of a line to check the key signature when I’m already several lines into the music, I’d be quite wealthy. I did this once while playing from a Salvation Army Christmas Carol book on Christmas Day. These tiny publications are printed on A5 paper so they can be mounted on a lyre while playing outdoors. To save further space, the key signature appears just once - at the very beginning of the piece. If you get as far as line two or beyond and realise you’ve forgotten to check the key, you have to shift your eyes even further to correct your omission!

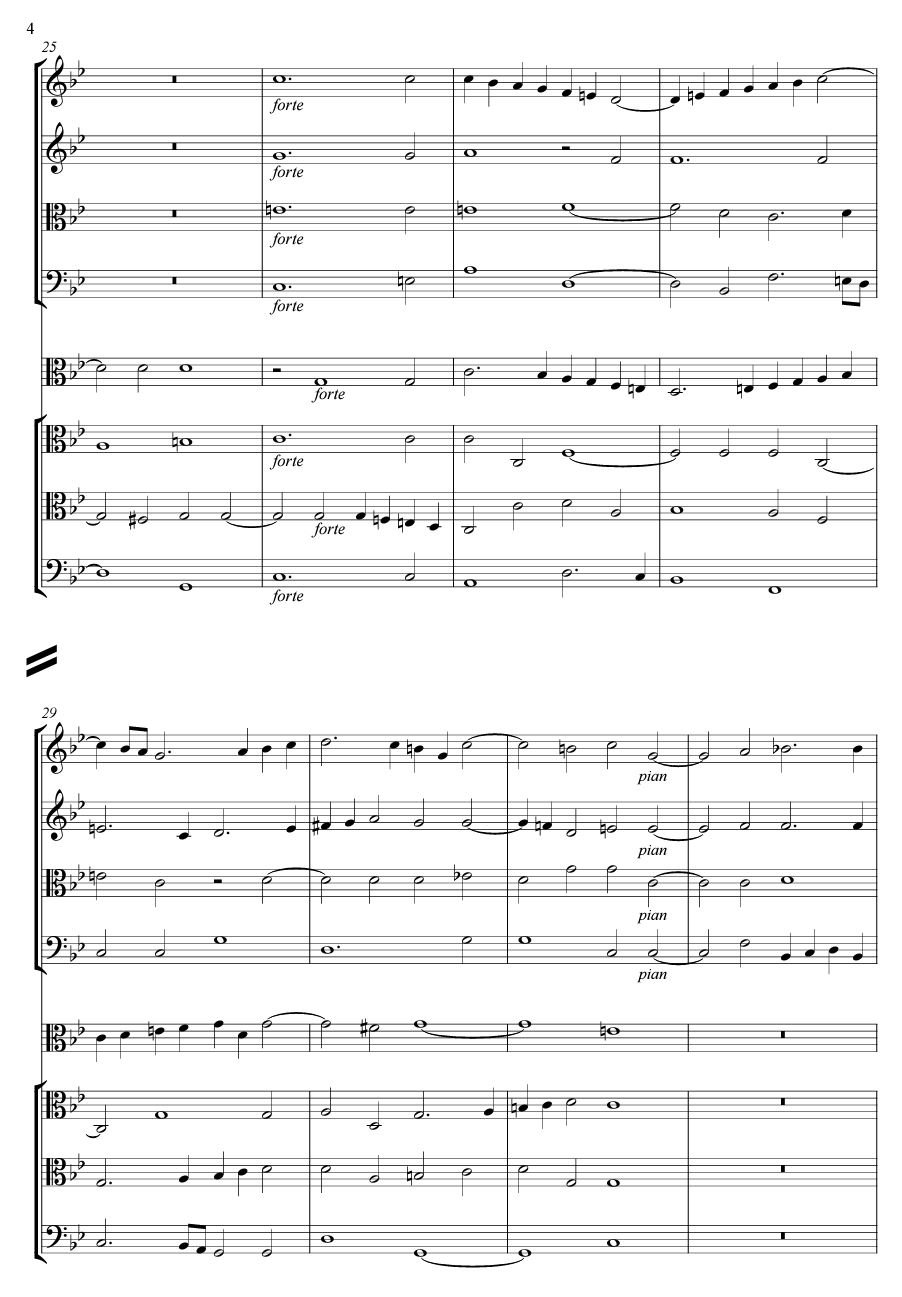

Of course time signatures can be problematic too, especially if you’re playing a piece of music where there are frequent changes. While playing in the orchestra for John Hawkes’ Concerto for spinet and recorder orchestra I didn’t dare take my eyes off the music as the metre changed every couple of bars. Doing so risked me planting them back in the wrong place to count a of 7/8 bar when perhaps it should have been 3/4. There might be only a single quaver’s difference between the two, but that’s enough to make or break a performance. I made exactly this error in rehearsal, but in concert kept my eyes firmly glued to the music!

“Sorry everyone. I’ll play the piece in 4/4 instead of 3/4 this time.”

Have you ever noticed the most difficult bars in any piece of music always coincide with a line break or page break? I swear music publishers collude to make this happen, just to keep us musicians on our toes. I can think of one example in a Bach Trio Sonata where two consecutive lines have almost identical music - a sure fire recipe for missing a line or playing one twice. I normally only write on music in pencil, but on this occasion a highlighter pen helped me distinguish between the two lines and avoid disaster.

Generally speaking, music notation has evolved to be as clear as possible, so we can read the dots quickly and efficiently. If there’s one detail which could do with a rethink it’s surely the symbols for minim and semibreve rests. A single symbol is an entirely different length, depending on whether it sits on the third line of the stave or hangs down from the fourth. That’s a recipe for chaos if you’re not concentrating and I’ve seen many musicians fall prey to this.

“Oops. I thought that was a whole note…this edition doesn’t make it easy to distinguish the semibreves from the breves” (Said while squinting and leaning closer to the score.)

While we’re on the misreading of notation, we’ve all failed to see dots beside or above notes - and the difference between those two things can be enormous.

“Wait, was there a dot there?!”

A bad workman blames his tools. Yes, it’s easy to blame the quality of notation or printing in an edition, but I can think of two distinct occasions where this has almost derailed a session I was directing. At one course I ran a class studying the Telemann Concerto in F for four treble recorders. 99% of those playing had one edition, but we quickly discovered a whole array of errors in the music. This was bad enough, but imagine my bewilderment when I realised that in newer re-prints the editor had removed some of the mistakes, but added in different ones! The resulting music making was peppered with mistakes, but to this day I have no way of knowing which were the result of user error and which were typographical glitches…

“I forgot to come in because I had a GP in the bar before.”

Early on in my career I nearly reached panic stations with a piece of Palestrina I’d set for a course. I had a copy bought several years earlier, while my students mostly had copies purchased shortly before the course began. We started playing and I struggled to understand why people were playing the wrong lines. Eventually the penny dropped and I realised the publisher, in their wisdom, had swapped two of the voices in the latest reprint of this double choir work (quite sensibly, as it happens). This made the layout more logical, but they failed to make any mention of it in the foreword and I’d assumed my older edition was the correct one. These days I like to think I’d have cottoned on to the problem sooner, but the experience put a large dent in my confidence and I’ve never conducted the same piece again since!

User error

One of the classic exclamations I hear all the time from recorder players, is a realisation that they’re playing in the wrong fingerings - for instance, C fingering when it should be F. In nearly forty years of recorder teaching I can honestly say this is a universal error. Only once have I taught a pupil who never confused C and F fingering and I think we can assume that particular student was an exception to the rule. I can go one better though…

At the Northern Recorder Course, a decade or more ago, I was offered the chance to play a sub-great bass recorder, alongside two other excellent musicians. At the time I didn’t regularly play C fingering from bass clef so it took a fair degree of concentration. The music went quite high in places and imagine my confusion when I found my notes at odds with those of my colleagues. After a little cogitation I realised not only was I playing in F fingering for these high notes, I was also reading the music as treble clef - no wonder it sounded awful!

“Oops, wrong recorder!”

What notes am I playing?

With most recorders, you play exactly what you see. But for some of the more obscure variants a degree of mental gymnastics is required. There may be some who read G alto or voice flute music by relearning the way familiar finger patterns relate to the notes, but most of us don’t play these instruments often enough to justify the lengthy learning process. Instead we learn cunning tricks to get around these transposing instruments. In the case of the voice flute, I pretend the music is really in bass clef and add three flats to the key signature in my mind. That gets me to the right pitches, but also means I rarely have a clue as to the note name for a given fingering. Faced with the voice flute it’s not unusual to hear me mutter to myself, “What note am I playing?”

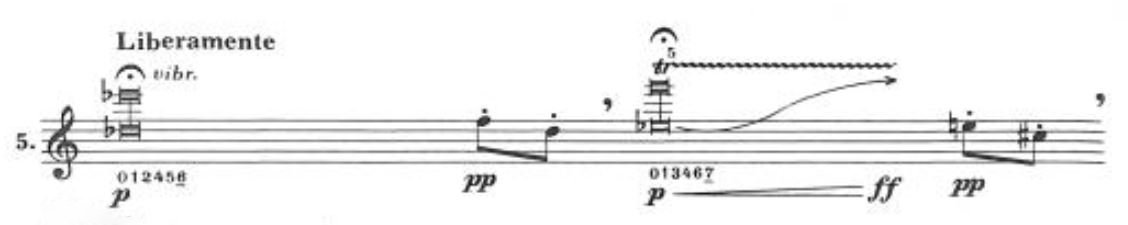

Terrorising trills & alternative fingerings

Another classic ‘excuse’ occurs in baroque music, with an exclamation of “I forgot the trill fingering”. I rarely get fazed by trills these days, but there are still occasional moments when I suffer a moment of brain-fade and plump for a completely wrong alternative fingering when aiming for a quieter dynamic. Thankfully this tends to happen in rehearsal (I’ve practised thoroughly to ensure it doesn’t happen in performance), but it’s still frustrating!

Accidentals or on-purposes?

I’ve always wondered about the name we gave to occasional sharps and flats beyond the remit of the key signature. We call them accidentals, and I can’t help feeling that’s a misnomer - surely they should be ‘intentionals’ or ‘on purposes’? Whatever they’re called, they’re behind a huge number of our musical excuses. After all, who can honestly say they’ve never forgotten an accidental that appears again later in the bar? I try to look ahead as I read music for the first time, so as to avoid such mishaps, but I’m not perfect and have often uttered apologies for missing one out. Of course, your best friend here is your pencil, so you can write them in and never forget again, but if you’ve been reading the Score Lines blog for a while you’ll already know I’m a big fan of pencils!

To repeat, or not to repeat - that is the question…

Here’s another classic - that moment when you go sailing on into the next section of a piece of music, only to realise that everyone has repeated the previous one. Yes, I’ll hold my hand up to this one - it’s so easily done.

One of my favourite light recorder pieces is Philip Evry’s charming arrangement of Gershwin’s Summertime. He crams so many different characters and musical styles into an arrangement where all the parts fit on a single page and to achieve this he includes a Da Capo and then a jump to the Coda at the end. As a conductor you may have spotted me frantically flipping pages back and forth to find my way, and I’ve long since lost count of the number of players I’ve seen forget one or both of these geographical changes!

“I repeated, but nobody else did...”

Slow, slow, quick-quick slow

As twenty first century musicians we’re used to most of our music being written in crotchet beats as it’s this sort of notation we first learnt at school. As we start exploring earlier genres of music we begin to encounter the concept of counting in minim or (horror!) semibreve beats. This presents the opportunity for an endless array of musical excuses, usually because we’re counting in one type of beat when everyone is doing something different. Added to that, music written in minim and semibreve beats looks very white and, to our modern eyes, very slow. I’ve heard many recorder players excuse their slowness because of the type of beat, as well as a few gasps of horror when they’ve realised how quick crotchets and quavers can be if you’re feeling a minim pulse!

Musician 1: “Are you counting in minims or crotchets?”

Musician 2: “Crotchets”

Musician 1: “Well, I’m counting in minims!”

Thinking can be overrated

As we learnt recently in my blog about practising, the body has an uncanny skill for learning repetitive tasks without the need for us to consciously think about it - often (erroneously) referred to as ‘muscle memory’. This is all very well, but there are times when I make the mistake of thinking about an action which is usually instinctive. At that point, if it all goes horribly wrong, you’ll almost certainly hear that age old excuse - “I shouldn’t have thought about what I was doing!”

Distractions galore

One of my favourite (accidental) tricks is to keep counting rests for too long, forgetting to come back in at the right time. The reasons for this are many and varied, but there are two that have tripped me up several times. The first is when I use the rests to listen intently to another section of the ensemble. As I luxuriate in the beauty of their playing, time drifts on and instead of stopping after eight bars, I find myself counting “Nine-two-three-four, etc” until the point when I realise I’ve missed the boat!

“I can do it on my own, but not when others join in.”

“I was listening to how lovely the tenors/basses sounded, and lost count.”

The second likely distraction comes when I’m rehearsing in a particularly beautiful or unusual concert venue. Here my inner architectural photographer kicks in and I either find myself marvelling at the way a modern building is constructed, or else I’m musing on the beautiful play of light in an ancient church. Either way, there’s still that “Uh-oh” moment of realisation and a frantic rush to catch up!

For other musicians there may of course be different distractions. This one, which came from a member of one of my recorder orchestras, made me smile…

“I was so busy looking at you (the conductor) that I lost my place!”

Human limitations

Aside from our musical limitations, we all have simple physical limitations, which often increase as we get older. It’s only in the last decade or so that I’ve begun to wear reading glasses over my contact lenses for close up work and you can guarantee they’re never to hand when I most need them. My trombone playing partner has recently acquired some special specs for reading music or computer work and I’ve lost count of the numbers of times I’ve heard him same the exact words sent in by one of my Score Lines subscribers…

“Wrong glasses!”

Evidently it’s not just recorder players who make excuses for their musical shortcomings - I’m sure brass players have many special excuses all of their own!

If there’s one thing that’s become a permanent irritation as I’ve aged it’s the shrinking bar numbers in my music. Yes, I know they haven’t really shrunk, but it often feels that way. Yes, I could put my reading glasses on and they’d be beautifully crisp, but I don’t need them for playing or conducting music (I can see the notes well enough) so instead I go through my scores pencilling them in larger. It’s a clunky and time consuming solution, but it works.

In search of the perfect thumbnail

While we have no say over the deterioration in our sight (or hearing, come to that) there’s one recorder-critical element of our bodies we do have control over, and that’s our left thumbnail. Yet, still we attend rehearsals only to realise cutting this single nail was the one thing we forgot to do before leaving home.

I’ve seen many a recorder with a once round thumb hole, now worn away to something ovoid in shape, and this can make high notes a complete magical mystery tour. My personal solution is to roll my thumb instead of pinching with my nail, but I know that technique doesn’t suit everyone. At least I can do this without worrying about the length of my nail, saving me from that perennial excuse - “My thumbnail’s too long.”

“I must get my thumbhole re-bushed”

Technology that trips us up

While human nature is responsible for many of our excuse making, technology can be a trigger too. I’m guilty of occasionally forgetting my pencil (or omitting to sharpen in) but I’ve encountered ensembles where one pencil is apparently shared by an entire section of players!

Sometimes our instruments are the brunt of our excuses. Perhaps you have a leaking pad on a larger recorder, causing low notes to be unreliable. Another favourite of mine is discovering at a crucial moment that my key isn’t quite in the right place for my little finger. I’m pleased to report this only ever happens in rehearsal - by the concert I’ve always got my act together and actually checked it’s positioned perfectly!

“My bottom C (tenor) isn’t working!”

The ultimate instrument related excuse is actually having the wrong recorder to hand. I have to confess I did this once at a friend’s wedding. I was playing some informal music with friends as the congregation arrived, an hour or so before the ceremony. One of our chosen pieces was the Chaconne from Purcell’s Dioclesian, which begins with a repeating bass line, after which the treble parts come in one after another. Imagine my embarrassment when I started playing my treble line, only to discover I was a semitone flat - I’d inadvertently picked up my A415 recorder, while the others were playing at A440. Much hilarity ensued and we thanked our lucky stars that it was still early, so only a handful of the congregation had been there to hear my utter incompetence!

A more modern cause of excuse making is the e-reader, which increasing numbers of musicians use instead of carrying round a heavy piles of books. I’ve yet to make this transition, but from your emails I can see these gadgets can provide a rich vein of excuses…

“The lighting on my e-reader hid that note…”

“Er… sorry, my page flip advanced the score two pages instead of one.”

And finally

I couldn’t resist sharing a handful more of your quotes, which either made me chuckle or gave me a flash of recognition…

From a recent orchestral rehearsal I conducted:

I was distracted by a spider.”

From an inadvertent soloist:

“Oops, sorry for that solo where we were meant to have rests.”

This one sounds life threatening, but I’m sure it’s a thought many of us have had when we weren’t concentrating properly…

“I forgot to breathe.”

So what can we learn from our shared compendium of musician’s excuses? Most importantly, none of us is perfect. We all make mistakes - some of them subtle errors that no one will likely notice but yourself; some of them great big howlers which leave us grimacing with embarrassment. Rarely will these mistakes be life threatening and I’ve even met audience members who love concert mishaps because it makes them realise we’re all only human - even the astonishing virtuosos we see in famous concert halls. The important thing is to learn from our mistakes and have some fun along the way.

I’ll leave you with two parting gifts. One was a request from Dr Winter, my harmony professor at Trinity College of Music. If we hadn’t completed the homework he’d set, we were instructed to at least have a creative excuse ready for him. For instance, “A swarm of bumblebees stole my harmony homework while I was riding the number 10 bus along Oxford Street” is much more entertaining than “I forgot” and shows some imagination, even if it has no bearing on reality. Next time you make a spectacular blooper, why not think up a really fantastical excuse, à la Dr Winter?!

Finally, here’s a priceless video from an informal concert in Amsterdam where the virtuoso pianist Maria João Pires finds herself faced with performing a Mozart Concerto… but not the one she’d been expecting. This is the sort of thing performing musicians’ nightmares are made of, but miraculously she recovers her composure and goes on to play with so much aplomb you’d barely know there was a problem. Next time you miss an F sharp, remember, it could be so much worse!