You like to think of yourself as an individual, don’t you? We all do, but the truth is we’re far more alike than we’re sometimes willing to admit.

When I began the Score Lines blog, just a few weeks ago, I started by sharing Walter Bergmann’s Golden Rules with you. Sadly I never met Walter, but I wouldn’t mind betting he came up with his pithy comments in response to situations he encountered when working with recorder players. Over the last three decades I’ve conducted and coached groups of recorder players of all ages and backgrounds and I too have found similarities in the mistakes they make. As a result there are phrases and tips that I find myself offering on a regular basis. Granted, my ‘golden rules’ may not be as pithy as his, but I wouldn’t mind betting Walter Bergmann would recognise some of the habits I encounter among players today!

Should you worry that you’re making the same mistakes as others? Absolutely not! While we all have different tastes, skills and characters, we are fundamentally made of the same stuff - it’s inevitable we’ll share some of our faults too. I hope there will be at least one nugget here which may help you identify and iron out some of your flaws. Remember though, none of us is perfect so don’t worry if you recognise your own playing in a few or many of my points. One of the best ways we can learn is through our mistakes, so you’re just taking steps towards a new, improved you!

1. Just wiggle your fingers and blow!

This may seem a very simplistic suggestion, but it reflects two things - our human inability to multitask and the way we tend to overthink what we do.

When working on a tricky piece of music it’s easy to be so focused on just getting your fingers and tongue around the notes that we forget to use sufficient air. As a result our tone quality suffers. I’ll often remind groups to think about their breathing and blowing as well as their fingers and it’s astonishing what a difference it immediately makes to their sound.

This isn’t the only situation where I’ll quote these words though. In lessons I often find pupils are so focused on playing every single note that they get stuck in a spiral of over-cautious, slow playing. Sometimes throw caution to the wind and have a go at that tricky passage up to speed - literally throw your fingers at the notes and see what happens! It’s a really useful way to take stock and discover how far your diligent practising has got you. Some bits will be surprisingly good, while the added burst of speed will reveal the areas which still need more work. Go on, be brave - just wiggle your fingers and blow once in a while!

2. How long is a minim?

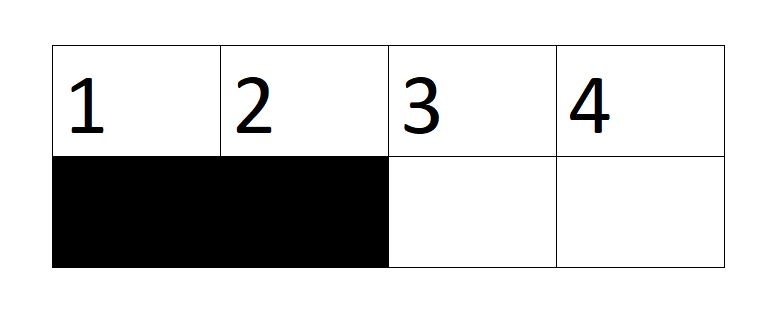

This is a question I often pose to groups and they look at me as though I’m asking the strangest question in the world! Of course, the answer is two beats. But how many beats do you need to be aware of when playing a minim? Then it’s three beats! Confused? Look at this graphic illustration of a minim note within a bar of four beats.

See how the minim begins at the start of beat 1 but doesn’t end until the point where beat 3 begins. Next time you have a long note followed by a rest, think about where the note ends as much as where it begins. Inadvertently shortening a long note can have a detrimental effect on the placing of what follows, especially if this shortening creates a big hole in the music. Equally, there will of course be places where you cannot hold a note absolutely full length because you need to breathe and still be on time for the next note, so this isn’t a ‘one size fits all’ tip.

3. Very few things in recorder playing can’t be improved by breathing

One of the greatest crimes in recorder playing is under blowing. Scrimping on the air you put through your recorder produces a weedy, undernourished tone and will compromise your intonation too. Remember, recorders are designed to be played with a particular flow of air. If you put less breath than this through your instrument some notes will be flatter than others. Groups I coach never fail to be amazed how much their tuning improves when they simply put use more air. A simple thing but with huge results. It’s easy to get hung up on desperately eking out your supply of air in order to get to the next breath mark. If this results in a weak tone you simply need to find an additional place to breathe.

If in doubt, open your mouth and breathe - your recorder will always thank you for it!

4. Finish your phrases with finesse

Do you ever have that feeling of “thank heavens I got through that phrase in one piece!”? Of course you do - we all have!

Now think about the final note of that phrase - how did you play it? Was it a much loved and beautifully shaped note, or a huge bump of relief? I bet it was the latter! Next time you’re playing, take care of all your notes - even the last one. Endings matter and a comment I once heard from a Royal Marines bandsman expressed this perfectly - “An audience can forgive anything, as long as you start and finish well and have shiny shoes”! Ok, I know (as did he) that’s a huge simplification, but you get the point. Always care about your music, right up to the last note.

5. Feel your dots actively

Back in the days when I taught the recorder in schools I’d often ask the children how many beats a dotted crotchet was worth in this rhythm:

A common response was, “One and a bit beats, Miss”. Not quite the precise answer I was hoping for, but it’s an approach I see in adults too. Of course, the correct answer is one and a half beats (unless you’re counting in 6/8, that is) – but how to do you count that half beat?

Most people understand the need to count ‘1, 2 and’ where the and is the quaver that follows the dotted crotchet:

However, in my experience, all too often musicians don’t feel that second beat actively enough. As a result, the quaver occurs in a somewhat nebulous timeframe, rather than precisely a beat and a half after the dotted crotchet. The solution to this problem? Simple – just feel the second beat more actively. Do this and you’ll know exactly where the quaver needs to be placed, then your rhythms will also knit together precisely.

6. Dotted notes and ties shouldn’t feel nauseous

Those of you who’ve worked with me in person know this is one of my favourite bugbears. If I had a pound for every dotted or tied note which had an ungainly bulge in the middle I’d be a millionaire. The reason this happens is because you’re feeling the rhythm and that is no bad thing. However, take care to feel the dot or the tie in your head, not through your breath. By all means allow your tone to build through a tie or dotted note, but do it with a progressive intensification rather than a nauseous lurch! If you’re not sure whether you have this bad habit, try recording yourself playing music which contains some of these patterns (the voice memo app on a smartphone is handy for this) and you may find it surprisingly revealing….

7. Always sight read at full speed

This is a piece of advice I was given by a fellow conductor many years ago which is absolutely true. When I run a new piece with a group of musicians I always begin at full speed. Yes, there will be plenty of wrong notes and other blunders, but it plants the correct speed in their minds. First impressions are important - think about the way we judge people based on first encounters. The same applies to music. If you start off slowly your brain will always remember the slower tempo. But if you jump in at full speed, warts and all, you’ll remember that and it’ll it easier to work back up to full tempo as you practise.

8. Are you watching carefully?

I know I’m not the only conductor who berates groups for not watching the beat closely enough. No doubt the practice of ignoring the conductor has been going on since we moved from thumping a stick on the floor to waving a stick in the air. But do you really need to watch every move the conductor makes? Actually, no!

In an ideal world I’d love it if you watched me like a hawk, taking in every little gesture thoughtfully created to help you play the music. But that sort of attention requires you to all but memorise the music and we all know that’s unlikely to happen. Instead, try putting your music stand at a height where you can see the music clearly but where you can also see your conductor in your peripheral vision. Next time you practise, take moment to focus on your music and note how much of your surroundings you are aware of at the same time. Yes, whatever’s in your peripheral vision isn’t clearly in focus, but trust me, you really don’t need to see me in perfect clarity! Just being aware of the movement of the conductor’s beat will help you keep better in time, and you can look up when necessary to take in other gestures.

9. Breathe in sympathy with the music

Imagine you’re about to play a fast piece of music – what body language clues do you expect to receive from whoever’s leading your ensemble? Almost certainly, a brisk lift of their instrument and a speedy intake of breath. How about if they move gently and take a leisurely breath in? I’m willing to bet you’d expect a slower tempo.

The way we breath when playing has a huge influence on our playing and the musicians with whom we play. Next time you practise, try taking different speed breaths and note how it encourages you to play the music differently. A slow breath implies a relaxed tempo, while a sharp intake of breath suggests something more dynamic. While you’re at it, do breathe in time with the pulse during the music and you’ll almost certainly play more rhythmically.

10. Don’t fight your recorder!

All too often I hear recorder players doing battle with their instrument.

On a Baroque recorder your bottom notes will naturally be soft, while the higher registers are louder and more piercing. You want stronger bottom notes? Try a Renaissance recorder, whose bore is wider at the bottom, resulting in fruitier low notes. The downside? You may have to sacrifice the ease of the highest notes. Every recorder is a compromise and this is the price we pay for choosing an instrument which hasn’t evolved significantly since about 1750.

Of course, not all composers understand this. We’ve all come across pieces where a bottom note is marked forte or a composer who demands a pianissimo top note. Instead of trying to force your instrument to achieve the impossible, I would encourage you to be sympathetic to your recorder and allow it to sing to its best ability.

Let me share a practical example with you….

Last week I rehearsed my recorder orchestra in a piece which ended with a piano low F played by the contrabasses, while the rest of the orchestra followed on with a chord above that. Players of big basses spend a lot of money to buy their instruments – effectively paying for the low notes other recorders cannot reach. Of course you want value for money, so I wasn’t surprised when my contra section gave that bottom F all they had, going for a full on fruity sound! Was it a pleasant effect? Frankly, no! Instead I encouraged them to soften their faces and throats, breathe deeply and blow in a gentle, relaxed way. What a difference! Suddenly we had a beautiful, warm but piano tone which didn’t set my teeth on edge. Even better, the instinctive reaction of the rest of the orchestra and their murmurs of approval showed they liked it too! As soon as the contras played their bottom F in its sweet spot, rather than trying to make it bigger than was practically possible, the effect was glorious.

My advice to you is to think about what is realistic and pleasurable when playing the recorder. Yes, you may not achieve the dynamics the composer demands, but the result will be much more enjoyable and your notes will sound better. Use a slower, gentle airflow for low notes to make a sweet, relaxed sound. For higher ranges plan ahead and be ready to use faster moving breath so your notes speak with ease. Play with sympathy for your instrument (and remember different makes and models of recorder have different needs) and you’ll play more beautifully.

11. Don’t be afraid of high notes

My clarinet teacher used to tell me that high notes need to be tamed in the same way you would train an over-eager dog. Rather than being hesitant, showing your fear, you need to be confident and assertive, showing them who’s in charge! The same principle applies to the recorder.

How often do you see a top note looming on the musical horizon and feel a cold stab of dread in your heart? What happens when you get to the note? I imagine you may well tense up, blow tentatively, tongue the note for all you’re worth and jam your left thumbnail into the hole in desperation. The result? If you’re lucky, a tight, squeezed tone and if you’re not, a complete disaster!

Here’s a better strategy….

Breath deeply beforehand, so you have plenty of fuel to create the faster airflow high notes demand. Think about just how fast the air needs to go before you hit the note – plan ahead. Tongue gently – high notes are far more likely to split if you hammer them out with force. Finally, think about your left thumb position. Open the thumbhole a small amount. Open it too far and the note will fail entirely, but close it too much and you’ll get a rough undertone. Better still, regularly practise plucking high notes out of nowhere – that way you’ll learn the needs of your instruments so you can find them with ease in the field.

12. Make your conductor happy by using your pencil!

If there’s a sound that makes me happy it’s the clink of a pencil being placed back on a music stand. Does this make me strange? Well, that’s for you to decide! Seriously though, there’s absolutely no shame in writing on your music if it helps you play better.

I write things on my music all the time. I know from experience that if I don’t, I’ll forget crucial details and will make mistakes. My rule of thumb is if I’ve made a mistake more than once I need to write a reminder in my music. Doing so ensures I don’t have to think so hard about the basics (accidentals which continue through the bar, the breakdown of tricky rhythms etc.) and instead I can focus on real music making.

I have a fascination about the way the human brain works and have recently read several books on the subject. It surprised me to learn that our short term memory is a minute or less. That means if you make a mistake while practising but then carry on to the end of the piece you may well have forgotten what that mistake was by the time you come to write a reminder in your music. Instead, stop straight away and make a note of that missed accidental, or incorrect rhythm.

One of the ways we move patterns and actions from short term to long term memory is by repeating them. If you continually come back to that same accidental and play it wrong you are repeating and compounding the error. After a while the mistake gets stored in long term memory. We all know from painful experience that bad habits are harder to shift than creating new good habits. Unlearning an error is more difficult than learning it correctly from the start as you are having to overwrite an incorrect memory with a new correct one. If my audience includes any neurologists you may well be cursing me for oversimplifying this complex subject by now. However, if my explanation helps even one musician play more right notes I make no apology!

While we’re here, please don’t write cryptic symbols in your music. Instead use words or symbols you’ll still understand in a month’s time. I once asked a pupil of mine what the exclamation mark written above a note in her score meant and she had to admit she couldn’t remember! If she’d used an accidental or a word whose meaning was obvious she’d have avoided making the same error over and over again.

So there you have a dozen of the things I find myself saying to recorder players everywhere on a regular basis. No doubt others will spring to mind as soon as I publish this week’s blog, but I hope these tips will at least make you think and help you play better.

Do you have any handy hints and tips you’d like to share with our recorder community? It doesn’t matter how large or small they are - if they help you they’ll help others too! Please do share your thoughts in the comment below – let’s see if we can all learn from each other.