With music, developments usually come through evolution rather than revolution – as in nature, changes happen gradually over time. Musical forms slowly mutate, sometimes changing their names and definitions along the way. Today I’m going to explore two types of music we often encounter as recorder players - the canzona and sonata - looking at the connections between them. In previous blogs where I’ve delved into dance forms we’ve stuck with one period of music, but the canzona and sonata will transport us from the Renaissance right up to the present day.

The Canzona

The Canzona (or Canzon) first emerged in the late 16th century as an instrumental complement to the vocal chanson. Its evolution began in Italy, where Frescobaldi composed lots of them for keyboard instruments and the Gabrielis (Andrea and Giovanni) were writing them for ensembles. Gradually the canzona spread across Europe and ultimately became popular with composers of other nationalities.

In its simplest form the canzona is a single movement, opening with a musical theme which the composer then varies and develops. This is often achieved by creating imitation between the parts – a technique later used in the fugue in a more precisely structured way. The extract below, from Giovanni Gabrieli’s Canzon Seconda, does exactly this, with the same melodic idea appearing in all four voices in turn, before the composer moves on to other themes. The rhythmic pattern he uses at the beginning is also very typical of canzonas from this period – a long note followed by two short ones.

Play along with Gabrieli Canzon Seconda with my consort video.

As the canzona evolved, composers began to add short sections with different time signatures and tempi to add variety, but these remained interconnected sections rather than separate movements. Most canzonas begin in duple (2) time, with later contrasting sections in triple (3) time. There’s often a mathematical relationship between the tempo of these contrasting sections – something I know many musicians find hard to calculate. I explored this topic in one of my earlier blogs, so if you’ve ever found yourself perplexed by the change from two to three you can find it here!

An extract of a Canzon by Frescobaldi, with linked sections in different time signatures and tempi:

Composers rarely specified the exact instrumentation for their canzonas during this period, opting instead for non-specific part names such as cantus, altus, tenore and bassus. This means they can be freely played on any instruments whose range matches that of the music and we should feel no compunction about playing them on recorders! In 1608 the entrepreneur Alessandro Reverii published a collection in Venice titled Canzoni per sonare con ogni sorte di stromenti, containing music by twelve different composers. The very title of this collection gives carte blanch for them to be played on wind, brass or string instruments and no doubt helped with sales too!

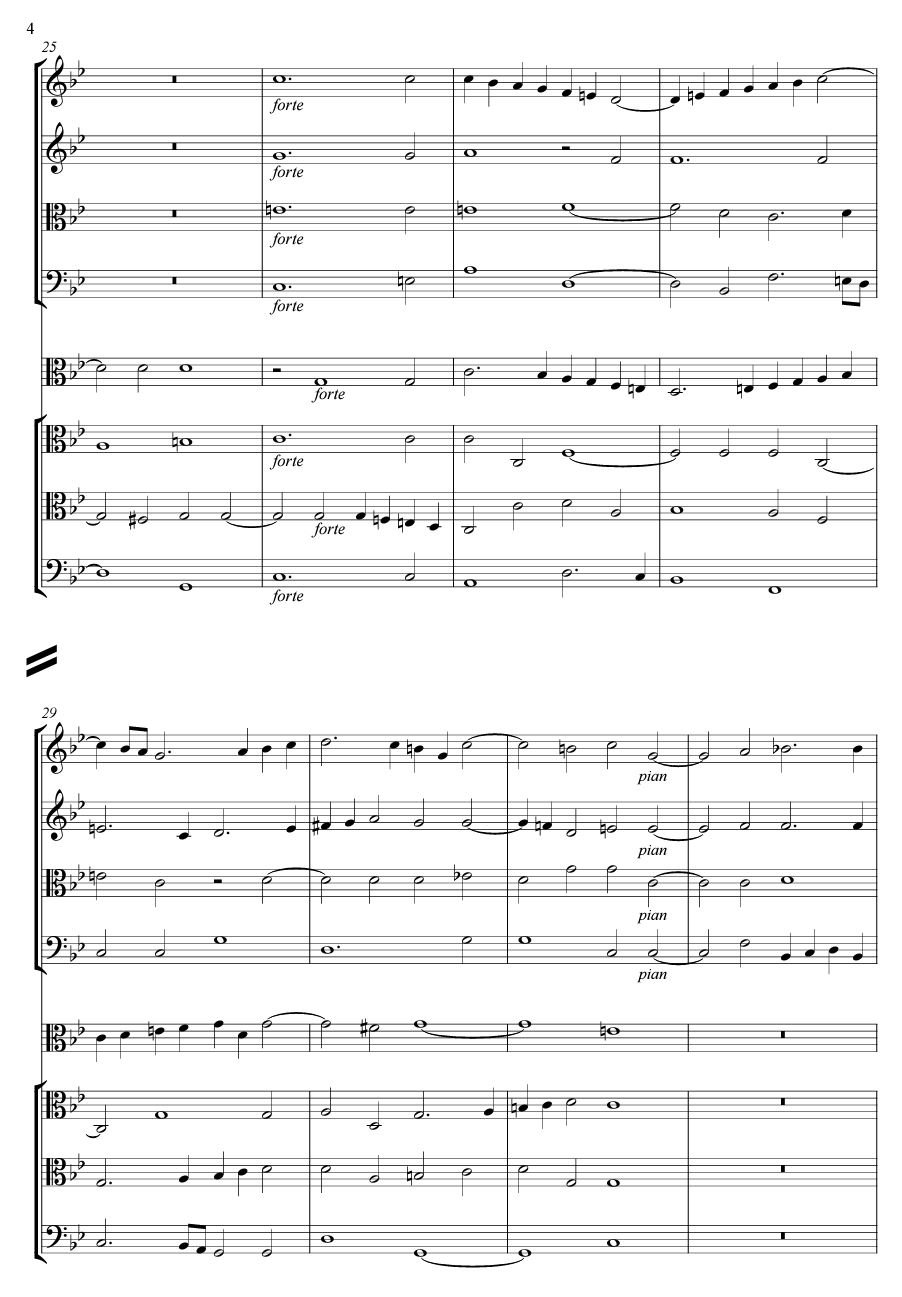

That said, some works do request specific instruments, including some of Giovanni Gabrieli’s later works. His Sonate pian’e forte (1597) specifies it’s to be played by two choirs of instruments – a cornetto and three trombones in one, balanced by a viola and three trombones in the second. This particular piece is notable for other reasons too. One is his use of dynamic markings (as you can see in the extract below) - a real rarity at this time. The second is title - Sonate. In spite of the name, it’s still fundamentally a canzona, rather than a sonata as we would understand it today, but it shows the direction in which music was moving. It’s worth remembering too that the word sonata derives from the Latin word sonare (to sound), implying it’s a work to be played on an instrument rather than sung.

Gabrieli Sonate pian’ e forte

Evolution of the sonata

The title page of Castello’s Sonate concertate in stil moderno per sonar

Gradually, in the middle of the 17th century composers began to separate the canzona's interlinked sections into distinct movements to create the sonata, and this became the dominant form of chamber music during the Baroque period. This change didn’t happen overnight, as you can hear from the recording of Dario Castello’s Sonata Prima below. Despite the name, the contrasting musical sections are still linked to each other in a single movement. This particular work comes from a collection titled Sonate concertate in stil moderno per sonar - Castello’s way of showing that he was exploring newer styles of writing. As a listener it definitely feels modern compared to the music of Gabrieli, but it’s still more closely related to the canzona than the sonatas of Handel and Telemann.

As the contrasting sections broke apart to form distinct movements, some of them would still retain the canzona’s imitative style. This is particularly true of faster movements, where you’ll often hear melodic material shared between the solo and continuo parts.

This little known Sonata in G by Andrew Parcham shows the further evolution of the form. Again, some of the contrasting musical sections run from one to another seamlessly, but there are also places when you sense the transition towards something with clearly separate movements.

When we finally arrive at the high Baroque the sonata emerges in two distinct forms - the Sonata da camera (chamber sonata) and the Sonata da chiesa (church sonata).

The Sonata da Camera has four movements: Slow-Fast-Slow-Fast - a format Telemann uses in many of his recorder sonatas. His Sonata in C from Der Getreue Musikmeister is a good example of the da Camera sonata:

The Sonata da Chiesa on the other hand, has just three movements: Fast-Slow-Fast. In this Bach Sonata for organ the da Chiesa format seems particularly appropriate, given it’s most likely to be played in a church. However, Bach also composed plenty of four movement da Camera sonatas too.

Ultimately the da Camera/da Chiesa concept is something of an academic distinction because a sonata can have any number of movements. Here are two more examples, starting with a Vivaldi flute sonata which has three movements but completely ignores the Fast-Slow-Fast rule!

And then there are sonatas like Handel’s Recorder Sonata in C major, which has five movements. These almost adheres to the da Camera, Slow-Fast-Slow-Fast principle, but then he sneaks in a Gavotte just before the final movement to show that rules are intended to be broken! Technically a piece made up of dance movements is a Suite rather than a Sonata, but it wasn’t uncommon for composers to blur the lines between the two.

Once the Baroque sonata had arrived, rules began to form regarding how it was composed. Usually a Sonata featured one or more solo instruments (as we saw in my recent blog post about trio and quartet sonatas) accompanied by a basso continuo team. This team often comprised of cello or viola da gamba plus harpsichord, but could be varied to use the organ as well as other plucked instruments, such as a lute or theorbo.

The form of the individual movements tends to fall into two categories. Many are through-composed, meaning they have just one continuous section, often using a musical theme which evolves through the movement. The other common format is Binary form which, as the name suggests, is made up of two sections (A and B), each of which is repeated - as you can hear in the first movement of Telemann’s Recorder Sonata in F:

Later sonatas

The sonata continued to evolve through the Classical and Romantic periods - a time when the recorder was sadly all but dormant. The first movement of the Classical sonata evolved from the simplicity of Baroque binary movements into the more complex Sonata Form, which followed an expanded ternary (ABA) structural pattern.

The two sections of the earlier binary form are now combined into one opening section as two contrasting musical themes, each in a different key. This opening section of a sonata form movement is called the Exposition. This is a followed by the Development, where the themes are added to and expanded upon, followed by a Recapitulation, which returns to some of the earlier musical ideas to round off the movement. Sonata form also became the dominant form for the opening movement of many works in the Classical and Romantic periods, including concertos, symphonies and chamber music (e.g. string quartets).

This Sonata Form movement is often the centre of gravity for Classical or Romantic sonatas as it tends to be the longest movement. It was usually followed by three other movements - traditionally a slow movement, a Minuet or Scherzo and culminated with a lively finale of some sort.

The Sonata in the 20th century and beyond

Sadly the recorder missed out on Classical and Romantic sonatas, but many contemporary composers since the recorder’s revival in the early twentieth century have chosen to write sonatas for the instrument. York Bowen (1884-1961) chose to write his Sonatina (a small sonata) in a positively Romantic style, while Lennox Berkeley went for a more contemporary feel. Composed in 1939, this work is one of the first sonatas written for the recorder after its revival.

During its evolution from the renaissance canzona, to the endless variety of modern sonatas, this musical form has undoubtedly covered a lot of ground.

Do you have favourite sonatas you return to regularly, either as a player or listener, for the recorder or any other instrument? Why not share your favourites with us in the comments below - it’ll be fascinating to learn which canzonas and sonatas make it into your personal playlists!