Think back to when you first started playing the recorder. Do you remember the simplicity of the earliest fingerings you learnt? Each note had one possible fingering and it was challenge enough to wrap your fingers around those.

In reality, how many different fingerings do you think there are for each note on the recorder? A couple, perhaps? You might be shocked to learn that some notes have dozens of possible fingerings, each used for different purposes. Today we’re going to look at the reasons why you might wish to learn some of the recorder’s many non-standard fingerings. How many you choose to learn, and the reasons for doing, so will depend on the level you’re at, but it’s useful to at least have an awareness of the principles behind them.

A word on numbering

I’m going to share lots of fingerings with you today, so it’s worth saying a few words about how these are notated. I’ll mostly use illustrative charts, but from time to time I’ll also use numbers. A standard has evolved in recorder tutor books for the numbering of the fingerholes, which is shown below. The left thumb is 0, while the holes on the front of the recorder are numbered 1 to 7, top to bottom. This may be different from other instruments you play - for instance the piano, where the fingers have different numbering patterns.

The standard fingerings we use every day produce a consistent quality of tone throughout the recorder’s range, with good intonation. In most situations these fingerings work perfectly well, but there are still occasions when we might need to tweak them a little…

What is a standard fingering?

If you consult the fingering chart provided with any new recorder it might be easy to assume there’s just one standard set of fingerings and anything else is an alternative. There’s a degree of truth to this, but in reality even standard fingerings can require a degree of flexibility. Those shown in your fingering chart are just a starting point.

Certain notes may need a little tweaking to play in tune - for instance low C sharp on the treble recorder (G sharp on descant or tenor). Most fingering charts will show the following fingering:

This generally works well, but may not always be perfectly in tune. To correct this, the simplest solution is to cover a little more or less of hole 6. For instance, my sopranino recorder needs finger 6 to be covering both double holes to be in tune in most circumstances. I learnt this a long while ago and using this slightly modified fingering is now habitual.

It’s worth remembering too, that unless you’re playing with a piano (where the pitch of each note is fixed by your piano tuner) the exact placing of any note will vary slightly, depending on its position within each chord. For instance, a C sharp which exists as the major third of an A major chord will need to be slightly lower in pitch than the same note used as the fifth of an F sharp major chord.

When you begin playing larger recorders (bass downwards), a little flexibility is often required, even with the so called standard fingerings. For example, on many bass recorders (especially plastic ones) the standard fingering for low E flat will be too flat. The fingering below is often a better choice, using finger 5 instead of 4:

Similarly, many basses are reluctant to play top C sharp with the fingering we would habitually use for the equivalent note on the treble recorder. The following is a much more reliable alternative, although curiously it tends to be out of tune on smaller sizes of recorder:

Setting these minor anomalies aside, why would you wish to use a different fingering if the ones you’re already using are serving you perfectly well? There are a number of reasons, so let’s take a look at some of them…

Ease of playing

The most practical sort of alternative fingerings are the ones we use to make life easier for ourselves. The recorder’s basic design hasn’t changed significantly over the last three centuries. The keywork which gradually developed on other woodwind instruments (flute, oboe, clarinet etc) during this period was intended to help extend the range of notes available and to make the playing of chromatic passages simpler. Our instrument is capable to playing fully chromatic music without these additions, but this does lead to some complex fingerings. Take, for instance, this forked fingering (treble E flat or descant B flat:

It produces a clear tone, but to move from there to the notes immediately above and below requires us to move several fingers up and down simultaneously. With practice doing this neatly is entirely possible, but at high speed it can still be a challenge.

For such passages there are a number of fingerings we can use to make life easier, minimising the number of digits to be moved. These alternative fingerings tend to be the ones we learn first, simply because they make our life easier. The ones shown below are the most commonly used alternatives, with notes about the places where you might find them helpful:

There are many more you can use - too many to include a comprehensive list here. I’ll point you in the direction of some useful sources of information later…

Trills and ornaments

Baroque music has always been a significant part of the recorder’s repertoire, and with that comes the need for trills and other ornaments. Many trills are playable using standard fingerings, but for some combinations of notes we have to find alternatives to make them possible. I wrote a blog about trills, their reason for being and how to play them better a while ago. If trills scare you, this is a really good place to begin - you can find my blog here.

Creating dynamic shape

One of the expressive challenges we face as recorder players is the limited dynamic range our instrument has. There’s a limit to how much you can increase and decrease your breath pressure to play louder and softer before the notes becomes unacceptably sharp or flat.

One way around this problem is to combine a change of breath pressure with slightly sharp or flat alternative fingerings. Let me explain the principles involved…

To play quietly - here you use a fingering which would ordinarily be slightly sharp, and then drop your breath pressure slightly to bring the note in tune and play softly. This fingering, for instance, is a slightly modified treble E flat (or descant B flat). By adding a couple of extra fingers and dropping your breath pressure it creates a beautiful soft treble D or descant A.

The following table illustrates the quiet alternatives I use most frequently when I’m playing. Don’t forget to combine these with gentle blowing!

To play loudly - here you need to find a slightly flat fingering (often by adding a finger or two to the standard fingering) and blow more firmly to keep the pitch true. For instance, for treble C (descant G) you could add an extra finger on your right hand to do this:

I won’t include a list of loud alternatives here as they are easier to figure out for yourself. Just try covering or shading one of the open holes to see how much of a flattening effect it has on the note and choose the one that suits your needs best.

While these principles are quite logical, you must also remember that dynamic adjustments are easier to achieve with some notes than others. For the lowest notes there simply aren’t many (if any) suitable alternatives, while for others there are dozens of possibilities! As well as learning these new fingerings you’ll also need to remember to adjust your breath pressure to modulate the pitch of the notes.

How easy you find all of this will depend on the level of your playing. If simply finding the ‘normal’ fingerings is still a challenge this may be a step too far for you yet. I wouldn’t expect to introduce such complexities to my pupils until they are reasonably advanced, so please don’t feel you’re a failure if the concept alone boggles your mind!

Special effects

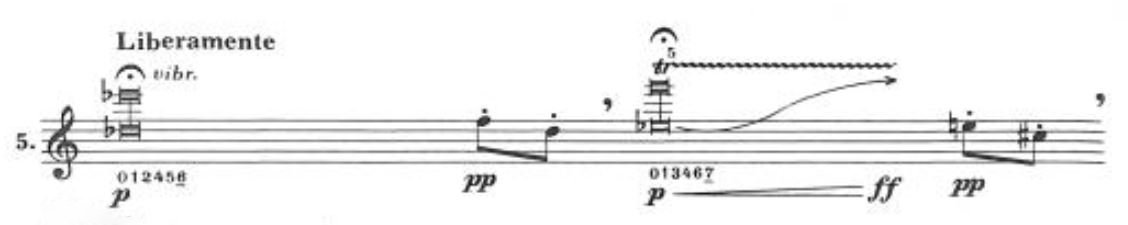

Another niche use for non-standard fingerings on the recorder is to create unique tonal effects - something most commonly found in contemporary music. For instance, in Hans-Martin Linde’s Music for a Bird he gives very specific fingerings to create special effects, such as a particular tone colour or to play multiphonics (playing more than one pitch at once), as you can see in the extract below. Such techniques are used in many contemporary works, but unless this is a style of music that particularly interests you, you needn’t worry about such fingerings in other types of music.

Resources to learn non-standard fingerings

Perhaps the most comprehensive source of recorder fingerings of all types is a website I only learnt about last summer - www.recorder-fingerings.com. Here you’ll find hundreds of charts for any type of fingering you could possibly wish for - for ease of use, dynamics, trills, and even for specific makes of recorder. It’s worth bookmarking this page so you can refer to it when you need a specific fingering. If you care to take a deep dive the site, it contains a bewildering array of options, but they’re helpfully arranged by category, making it easy enough to find exactly what you need.

If you prefer books to online sources, I can recommend two containing comprehensive charts for different uses:

Eve O’Kelly - The Recorder Today (Cambridge University Press, 1990).

A fascinating book about all aspects of the recorder, with a slant towards contemporary music. Still available to purchase new, but there are also plenty of used copies available at AbeBooks

Anthony Rowland-Jones - Recorder Technique, Intermediate to Advanced (Peacock Press, 2013)

A handy book covering all aspects of technique, including a comprehensive chapter on alternative fingerings. Available direct from the publisher or to order from most good bookshops.

Getting to grips with non-standard fingerings

It can seem bewildering when you first begin using alternative fingerings – there are just so many of them to get to grips with! To help you with this process, here are some of my top tips to get you started.

Start gradually

Don’t try to assimilate lots of new fingerings at once – that’s a recipe for disappointment and confusion! Instead, be selective. Whether you’re trying to learn an alternative fingering to make a difficult passage easier, or a specific trill fingering, begin by selecting just one or two. For instance, if you want to become fluent with the alternative E on the treble recorder (B on descant or tenor), choose a simple piece and practise using that fingering every time an E crops up in the music.

If you’re beginning to add trills into Baroque music, don’t feel you need to include them all at once. Maybe pick one trill that occurs several times in your music and play only that one to start with. When you’re comfortable and are able to locate the right fingering reliably, then add in another one. Because recorder music tends to use a limited range of key signatures, you’ll notice some trills crop up much more often than others. Use this to your advantage and learn them gradually. There are no prizes for trying to wrestle them all into submission at once, especially if you fail!

Get to know your recorders

While plastic recorders are mass produced and identical, wooden ones tend to have at least an element of individual human work in their manufacture. Made from a living, breathing material such as wood, even supposedly identical models can vary, so you may find you have to use subtly different fingerings from instrument to instrument. Take some time to make friends with each of your recorders, listening to the tone and intonation of your fingerings.

Listen out for tone quality

Some alternative fingerings have a different tone colour to their standard companions. For instance, cover your thumb hole and finger 1 (the fingering for E on treble, B on descant/tenor) and really listen to the quality of the sound - it produces a clear, solid tone. Now compare that with this alternative:

Do you hear the difference? The tone quality isn’t quite so clear, and on some recorders it may be a touch flatter in pitch.

Now consider the context in which you might use this alternative fingering. The obvious place is when you need to move swiftly (and perhaps repetitively) between E and the F (B and C on descant). If you’re doing this at speed, the difference in tone quality will be barely perceptible. But in slower music, where you may linger on the note for longer, its lesser tone quality may stick out like a sore thumb. In such situations it’s better to practise until you can use the standard fingering cleanly. If you’re adding an alternative fingering to make your life easier, be careful you’re not doing so at the expense of a consistent tone quality throughout the musical line.

Don’t neglect your intonation

When you start using sharp and flat fingerings to create dynamic contrasts you introduce another variable into the mix - an adjustment to your breath pressure. Over time you’ll learn to increase or decrease your breath appropriately, but it’s important to focus on tuning. You could practise this by playing with other people (or comparing your notes to the pitches on a piano if you have one). If neither of these is a realistic option, it’s worth investing in a tuning meter to help you. Standalone tuning meters can be bought quite inexpensively, sometimes combined with a metronome. But if you have a smartphone the simplest and cheapest solution is to download a tuning meter app. Using a tuner you can check the pitch of your piano and forte alternative fingerings and learn to modulate your breath pressure appropriately.

Elegantly dovetailed phrase endings

If you regularly play duets with a partner you’ll often find your phrases finish on the same note - particularly in Baroque music. If you’re both using the same fingering it can result in a final note which is suddenly much louder than those around it. To avoid this sudden bump a good solution is for one player to use a quiet alternative fingering, while the other sticks with the standard fingering. When I play with my friend Sophie in The Parnassian Ensemble we use this technique a lot to create smooth endings that don’t jolt the listener’s ear, and we both have favourite fingerings we know work well on our recorders. This is not a technique for elementary players, but if you’re looking to hone your phrase endings elegantly it’s worth experimenting with.

~ ~ ~

Have I opened your eyes to some new musical possibilities? Or are you feeling bamboozled by an unexpected array of alternative fingerings? Learning even a few of these fingerings can be a helpful addition to your technique, be they for trills, dynamics or simply to help you get around a tricky passage. The most important thing is it to begin your explorations of alternative fingerings gradually. Don’t try to learn them all at once - you may find yourself feeling lost and confused. Instead, be selective, picking just one or two at first, only adding more as you gain fluency and confidence.

Whether you’re new to this, or a real alternative fingering geek I’d love to hear about your experiences in the comments below. Do you have your own tips or perhaps favourite fingerings you wouldn’t want to be without? Please do leave a comment and let’s see if we can all learn at least one new fingering today!