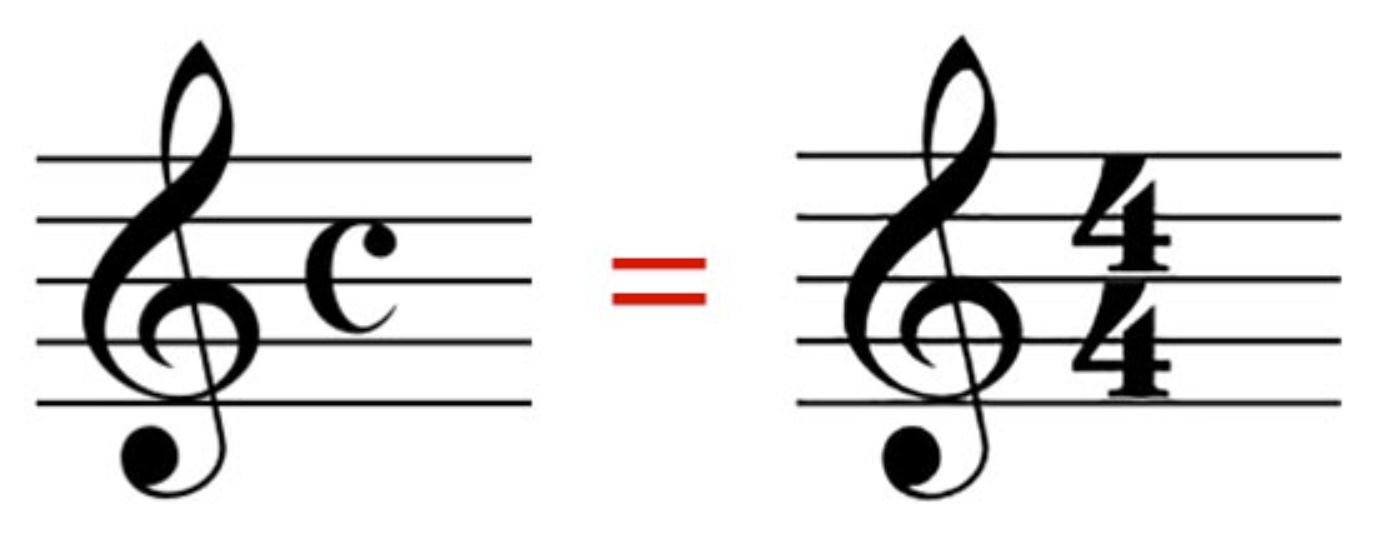

Having started my series of blogs about the theory of music with time signatures, the next logical step is to look at key signatures and the way composers use them. I know many amateur musicians have no formal training in music theory, so we’ll begin with the absolute basics. You’re welcome to skip ahead through sections you already know, or use them as a refresher.

The geography of key signatures

Let’s begin with the layout of key signatures. In most recorder music we rarely venture beyond three sharps or flats but it does no harm to check out the entire range of keys, especially as they are all interconnected. For starters, the key signature always appears directly after the clef and before the time signature. This pattern of clef then key signature is repeated on every line as a handy reminder.

Key signatures contain either sharps or flats - never a mixture of the two - and they always appear in the same order and layout. For sharps this order is F C G D A E B and for flats it’s B E A D G C F. Knowing this means you never need to think about exactly which sharps or flats are in your key signature. For instance, if there are three sharps they will always be F, C and G - no exceptions.

Perhaps the easiest way to learn this it to remember the following phrase, in which the first letter of each word gives you the order of the sharps:

Father Charles Goes Down And Ends Battle

To remember the order of the flats, all you need to do is reverse the phrase;

Battles Ends And Down Goes Charles’ Father

Now let’s take a look at the layout of the sharp and flat key signatures in the two clefs we use most when playing the recorder. The sharps and flats are kept close together on the stave and apply to every instance of a note - not just the ones which appear on the same line or space.

Now you know the order of the sharps and flats we need to look at the keys themselves.

Major and minor

As you’re probably aware, every key signature is connected to a major key and a minor key. For instance, a key signature of one sharp could be G major, but it could also be E minor. The latter is often known as the relative minor of G major because it is related by having the same key signature.

We’ll look at the difference between major and minor keys in a moment, but first let’s familiarise ourselves with the pattern of these keys.

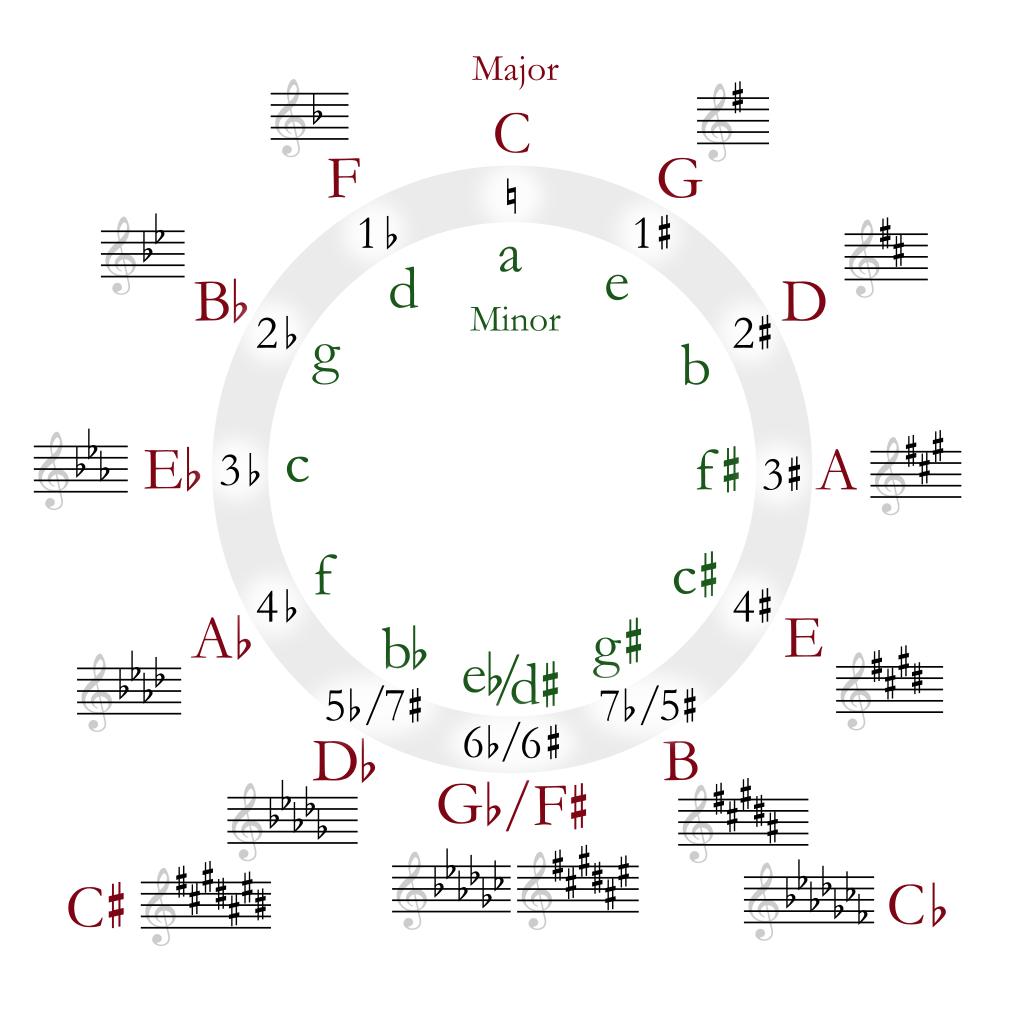

You may have heard other musicians talk about a cycle or circle of 5ths without really understanding what this means. This term is often used because each new key signature is five steps away from its neighbours. For instance, if you count up five notes from C (always include the note you’re counting from the note you’re counting to in the five: C-D-E-F-G) you reach the note G. This is the distance between each of the keys when you either add another sharp or reduce the key signature by one flat.

This is most clearly illustrated by looking at it in a circle. The major keys are shown on the outside of the circle and the minor ones inside. By working around from the top of the circle in a clockwise direction, a 5th at a time, you progress from one key signature to another, ultimately returning back to C major. It’s with noting that there’s some duplication at the bottom of the circle, where we reach the really extreme keys. For instance, D flat and C sharp sound the same, but you can have a key signature for either note - one has five flats, the other has seven sharps.

As recorder players, we’re unlikely to be worried by G flat major too often, but it’s useful to be aware of the existence of these extreme keys and to understand how they relate to each other. I would still recommend you practise scales in some of the more extreme keys to gain a fluency with the less commonly found sharps and flats. That way, when you encounter a stray D flat somewhere you won’t be thrown by it and have to stop and think about where to find it. Earlier this year I wrote a blog post about using scales and arpeggios in your practice - if you haven’t already read it, you can find it here.

Identifying your keys

It’s all very well knowing you’ve got four sharps to play in your music, but next you need to know the name of that key. Again, there’s a quick and easy way to work this out without having to memorise every single one. Let’s look at the major keys first:

For sharp major keys, the name of the key is a semitone above the last sharp of the key signature. So if you have four sharps, the last one is D sharp and therefore you’re in E major. Likewise, if the last sharp in your key signature is E sharp, the key is F sharp major.

For flat major keys, it’s even simpler - the name of the key is the penultimate flat of the key signature. Therefore, if you have two flats (B and E) you are in B flat major and if there are five flats (BEADG) you’re in D flat major. Admittedly this solution doesn’t work for F major, which only had one flat, but it’s one of the most common keys in recorder music so I dare say you’ll probably remember that one!

OK, that’s the major keys dealt with, but how to identify your minor keys? If your piece is in a minor key, there are will almost certainly be extra accidentals (usually sharps or naturals) dotted around in the music. We’ll look at the reason for these later. These should immediately alert you to the fact that the music is in a minor key, and you’ll probably be able to hear the different character of the music too. To figure out which key it is, use the rules I mentioned above to identify which major key is associated with that key signature. From there it’s an easy enough step to work out the related minor key, which is three semitones lower. So if the major key is G major, those three semitones are G to F sharp, F sharp to F natural and F natural to E. Your related minor key is E minor.

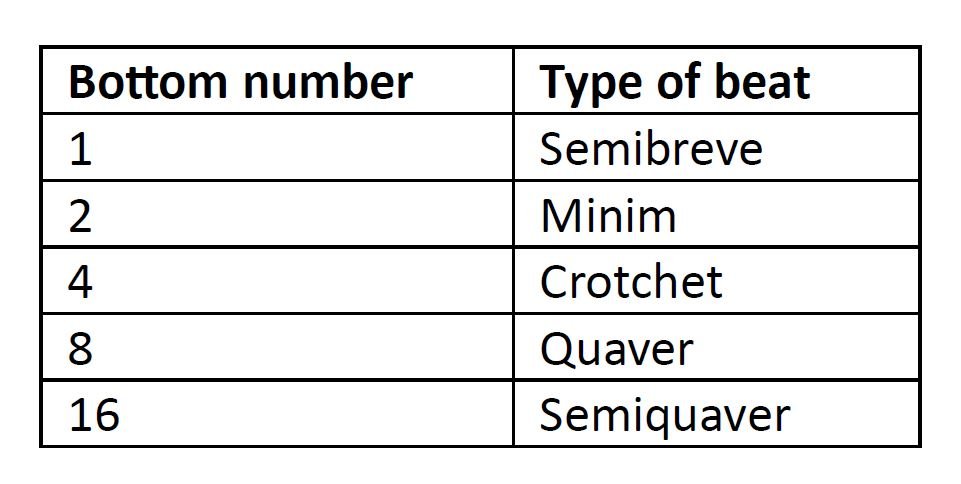

So you can see these rules in action, here are all the key signatures together:

Quick refresher - tones and semitones

Before we go on to look at major and minor keys in more detail it’s worth having a quick recap on tones and semitones. In western music the semitone is the smallest distance between two neighbouring notes - the equivalent of moving between neighbouring black and white keys on the piano. From a non-keyboard player’s perspective, a semitone is the distance between a natural note and its flat or sharp neighbour - e.g. D to D sharp.

A tone is a step wider - two semitones - as you can see from the keyboard illustration below. Semitones are shown in red, while tones are shown in blue.

These two intervals are the building blocks for all major and minor scales, creating the sounds we hear in major and minor keys. It’s important to understand the distinction between these if we’re going to understand the difference between the different types of scales.

Shades of major and minor

We often talk about music being in major or minor keys but have you thought about the difference between the two? We’ll get into the technical differences in a moment, but the most important distinction is the way they make the music feel. One of the ear tests often given in music grade exams is making the distinction between major and minor when listening to music, and teachers often ask students to decide if the music makes them feel happy (major) or sad (minor). This is, of course, a huge oversimplification - there are plenty of sonorous, serious pieces of music in major keys, or lively dances in minor keys. Perhaps a better distinction might be to think of music in a minor key as having a ‘darker’ sonority and major as being ‘brighter’. Let’s have a listen to some examples:

One of the most joyful and energetic examples of recorder music in a major key is Vivaldi’s Concerto, RV443, played here on the descant recorder by Lucie Horsch.

In contrast, the Welsh traditional lullaby Suo Gan is very poignant and thoughtful, but is still unmistakably in a major key.

And now two examples of music in a minor key. The first movement of Bach’s Double Violin Concerto is in D minor but is still full of life and energy, yet it definitely has a darker feel.

Perhaps one of the archetypal pieces of minor key music is Elgar’s melancholic Cello Concerto, composed soon after the end of World War I. The opening is heart wrenchingly sad, but even here there are moments of vivacity in the scherzo.

What’s the difference?

While we respond differently to music in major and minor tonalities, it’s also useful to understand the technical distinction. The key difference is the distance between the first and third notes of the scales, although as we will see there are other distinctions too. In a major scale, the distance between notes 1 and 3 is a major third. By contrast, in a minor scale the interval (distance) between these same notes is a minor third.

A minor third is made up of three semitones, while a major third is a semitone wider. Why not play the two examples below and hear the difference for yourself?

Of course there are other differences too, so let’s take a moment to look at the make up of major and minor scales.

Major scales

Major scales come in just one variety and the notes are the same whether the scale is ascending or descending. As you can see from the red boxes in the example below, each major scale contains two intervals of a semitone - between notes 3 and 4, and again between notes 7 and 8.

Minor scales

The minor scale has three different sub-species, as you can see below. The natural minor includes just the notes contained within the key signature. A natural minor scale is fundamentally the Aeolian Mode, but modes are a rabbit hole I’ll save for a future occasion or you might still be reading at midnight!

Like the major scale, the natural minor contains two semitones, but this time they occur between notes 2 and 3 and again between notes 5 and 6.

The Harmonic Minor scale tends to be the one most people learn first, although it’s used less than the other two in western classical music. When children begin preparing for grade exams they have to learn scales and arpeggios from memory and I think many teachers start with harmonic minors simply because they’re easier to memorise. This is practical solution, even if melodic minors are arguably more practical use in the music we tend to play every day.

As you can see in the example below, in a harmonic minor scale note 7 is raised by a semitone - in this case the F becomes an F sharp. This creates a semitone between note 7 and the key note, which creates a clear sense of pulling one’s ear towards the scale’s final destination.

The addition of this accidental also creates another interesting interval, marked here with blue circles - is an augmented second. This stretched shape in the musical line creates a more exotic feel - much like the melodic shapes you’d hear in the tune from a snake charmer’s flute.

If you want to hear the harmonic minor scale in use, Gustav Holst’s Beni Mora contains oodles of them from the outset. It was inspired by the music he heard on a visit to Algeria and instantaneously feels exotic to western ears, despite its orchestral soundworld.

Finally, we have the Melodic minor scale which is the variety we meet most often in the music we play. As you can see in the example below, both the 6th and 7th notes are raised by a semitone on the way upwards, and lowered back to their native pitch as the scale descends again. This means the semitones occur in different places on ascent and descent, but the effect is a very easy ‘melodic’ sound.

The Overture to Mozart’s opera Don Giovanni is a beautiful example of minor scales in action, definitely rooted in the dark, melancholic toneworld of the minor key. In this recording, 33 seconds in we hear small sections of melodic minor scales (listen out for those exotic augmented seconds) and and 1 minute and 12 seconds there are chains of melodic minor scales, rising and falling in the flutes.

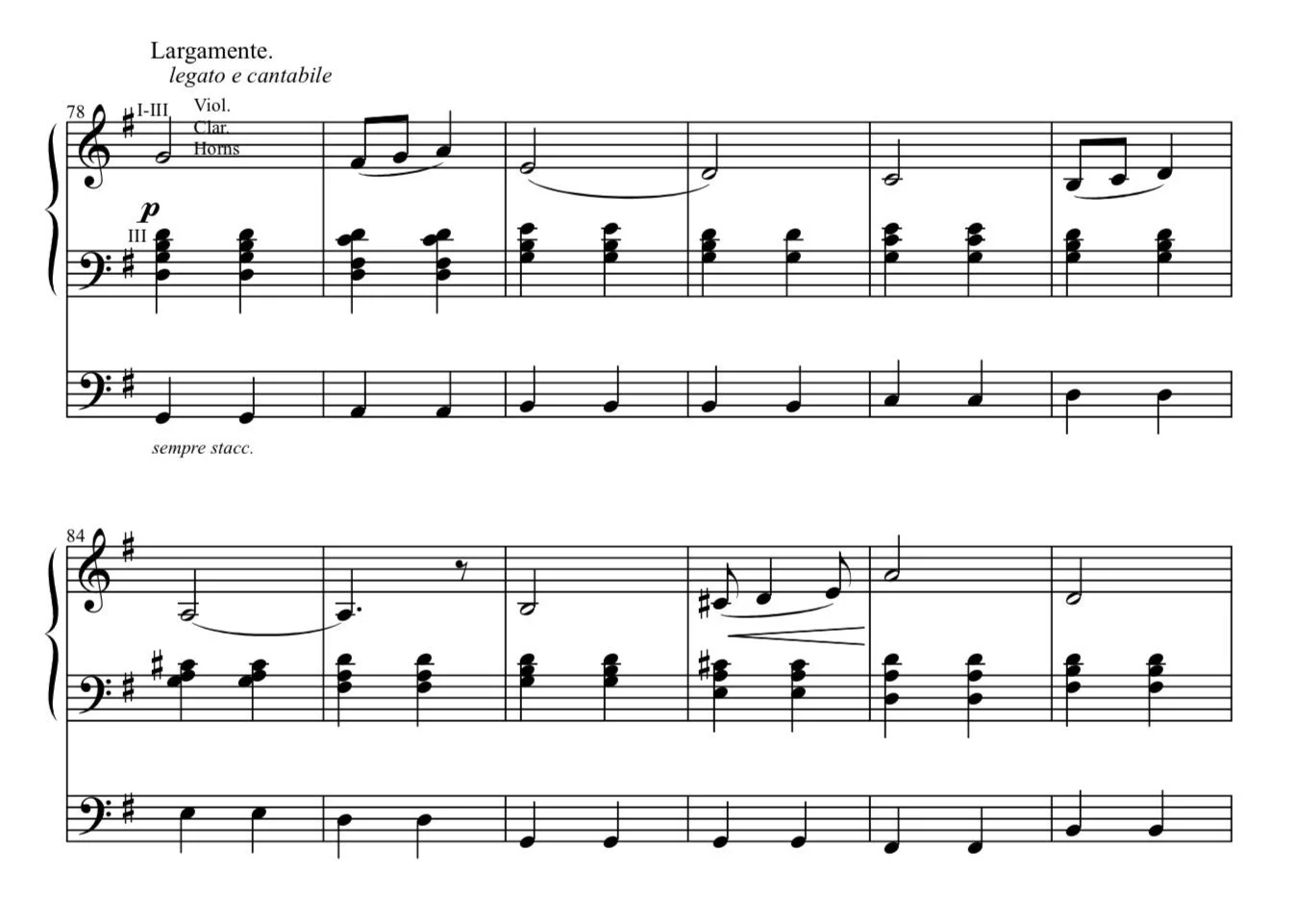

A Baroque quirk

Having talked about minor key signatures and the way minor scales are constructed I should perhaps mention one small glitch in the system. This occurs specifically in minor keys with flats in the key signature and mostly in Baroque music. As we’ve seen already, in a melodic minor scale (the type which occurs most frequently in Baroque music) about 50% of the time the 6th note of the scale is raised by a semitone. Therefore from the perspective of someone writing out music, or engraving plates for printing, there will be lots of occasions when you have to insert an accidental. Because of this it’s not unusual to find music from this period where the final flat of the key signature (looking at it from our 21st century perspective) is omitted.

For example, this extract from Barsanti’s G minor recorder sonata has only one flat in the key signature. Had the E flat been included, the engraver would have then needed to add flat accidentals for all the notes circled in red. Of course, the other side of the coin is that he or she then needed to add E flats in for all the notes circled in blue! One could argue for or against this Baroque practice, but it’s important to know about its existence when trying to understand the key your music is written in.

The false relation

No, this isn’t one of those family friends you always called ‘uncle’ when you were a child, even though he was really nothing of the sort! Instead it’s the name for a harmonic curiosity that crops up in early music; in particular repertoire from 16th and early 17th century England. You’ll often find it in music by Tallis and Byrd but Henry Purcell had a penchant for this piquant effect too.

You remember I talked earlier about the way a melodic minor scale has raised 6th and 7th notes as it ascends, returning them to their original pitch again as the music descends? Well, occasionally composers created melodic lines which did both at the same time. Sometimes you’ll get a direct clash as the raised 7th and lowered 7th occur simultaneously, creating one of those ‘double take’ moments as you try to figure out if someone played a wrong note. On other occasions it’ll just be a ‘near miss’ and the effect isn’t quite so astringent. There’s nothing to be done here, except to check the score to reassure yourselves that all is well and then simply enjoy the exotic clash in the music!

As you can see in this short extract from Byrd’s Ave Verum Corpus, a G sharp and G natural come into direct contact, albeit fleetingly, in bar 37. The music is in A minor, so the tenor line has the raised 7th note of the melodic minor scale (leading upwards to A), while the bass has the G natural which is descending. The fact that the two happen simultaneously creates a beautiful, piquant discord.

Endlessly evolving keys

While I’ve talked here about the relationship between key signatures and scales, in reality it’s unusual for a piece of music to remain in one key throughout. The process of moving between different keys is modulation. In order to explain this fully a knowledge of harmony and cadences is ideally required, but again that’s a large topic for another day.

From a player’s perspective the important thing is to look out for accidentals in your music. Yes, there are certain accidentals you’d expect to find in minor keys (specifically your raised 6th and 7th notes) but if you start to encounter additional sharps or flats it’s likely the music has modulated to a new key. You need to be Hansel, following the breadcrumbs through the forest in Hans Christian Andersen’s children’s tale. Look at the clues in your music - perhaps you’re in G major, but suddenly lots of C sharps begin appearing and the likelihood is the music is moving from G into D major, which has both F and C sharp in the key signature. Or perhaps, in the same G major piece the new accidentals are D sharps. In that case E minor is a more likely destination, with the D sharps being the raised 7th note of the scale.

Music often shifts to keys that are fairly close to home - perhaps the relative minor or just a step or two around the circle of 5ths I talked about earlier. With the tools I’ve given you today you are better equipped to follow the breadcrumbs and figure out where the music has migrated to. Here’s a final example to illustrate my point. In the first page of Telemann’s Recorder Sonata in F major he moves the music through no fewer than four keys. I’ve annotated this extract with different colours to show the important accidentals and the keys the music modulates into. Some of them are fleeting, while others feel more significant. You can click on the music to see it enlarged.

Over to you…

Equipped with this knowledge, you can now take it out into the world and use it to help you understand the music you play in a deeper way. If the concept of identifying modulations seems overwhelming for now, why not simply make a point of looking at the key signatures you encounter to identify where you begin? When faced with a new piece of music, take a moment to decide which key it’s in. The key signature itself is a big clue, and this might be all you need if the music is in a major key. If you spot some accidentals too, see if they fit in the melodic scale of the minor key with the same key signature and be ready for some darker, more melancholic tones.

Did you learn something new today? If the answer is yes, I hope my words have demystified music a little more for you. But if there are still gaps in your knowledge which need filling do leave a comment below and I’ll do my best to help you. This is an ongoing series of blog posts which I hope will collectively help you gain a deeper understanding of the music you play.