What comes into your mind when you think about scales and arpeggios? Perhaps memories from childhood - being nagged by a teacher to practise? Or maybe even a degree of perplexity about exactly what they are?

Many of us have a love/hate relationship with scales. When I think back to my teenage years I realise I owe my music teachers an apology for my lack of application when it came to these fundamental exercises. Time and again I would spend the last two or three weeks before a music exam frantically cramming my scales and arpeggios instead of learning them gradually over a longer period, Fortunately for me, I had an uncanny ability to learn them at speed and I usually got away with this last minute feverish rush of learning. The downside was that I never really absorbed them thoroughly, so within a couple of weeks of the exam I’d forgotten them all again! My slapdash approach must have been infuriating, but those teachers I’m still in touch with seem to have forgiven me!

Of course the irony is I’ve seen the same situation from the other side of the fence many times during my teaching career, quietly trying cajoling my students to start learning their scales and arpeggios as early as possible…

What are scales and arpeggios?

The first movement of Telemann’s Sonata in F major which is built upon lots of scale patterns.

Scales and arpeggios are the fundamental building blocks of music and all western music is created from these patterns. A scale uses neighbouring notes, while an arpeggio uses the 1st, 3rd and 5th steps of a scale to create a broken chord, where the notes are played in turn to create a melodic line rather than as harmonies.

Major and minor scales contain eight different pitches within each octave, arranged in a particular combination of tones and semitones. On the other hand, a chromatic scale includes all 12 notes - just as you would if you played every black and white note in order on the piano.

You’re probably most familiar with the concept of major, minor and chromatic scales, but there are many more types besides. Pentatonic scales have just five notes (sound just the black notes on a piano and you’re playing a pentatonic scale), modes are created from the patterns made by playing the white notes of the keyboard in different combinations, and jazz musicians have their own varieties of scales.

They’re not just a feature of western music either - in some musical cultures other patterns are used. For instance, Indian music is based on ragas - scale patterns which can include intervals even smaller than our semitone.

Why do I need to learn scales and arpeggios?

This is a cry many teachers have heard from their students in frustration! While they may not seem terribly exciting, learning scales and arpeggios helps your music making in many different ways. Let’s look at some of them…

They help you gain fluency

If we’re to play music with ease and speed, fluency is vital. Getting to the point where your fingers automatically find the patterns needed for each note at speed will allow you to tackle ever more challenging repertoire. If you have to stop and think about which fingers to move before each note (as a total beginner might) your musical lines will lack a sense of flow.

Improve your sight reading skills

Because music is made up of scale and arpeggio patterns, being able to recognise and fluently play these combinations of notes helps you read unfamiliar music more easily. If you want a comparison, it’s a bit like learning to read text. When we first learn to read we recognise the individual letters. Gradually we learn that these letters often appear together in particular combinations so we begin to recognise syllables and ultimately whole words and sentences. The notes of a scale are like the individual letters, while a scale is a long word or sentence which we take in at a glance through familiarity.

Coordinating finger movements

One of the big challenges of recorder playing is the complexity of the fingerings. Modern wind instruments have keywork to help simplify the finger patterns. Recorders lack these, so instead we have to play complex forked fingerings (for instance B flat on the descant or E flat on treble recorder). Shifting between neighbouring notes can often involve moving multiple fingers up and down simultaneously. We can use scales and arpeggios to practise this and make our finger changes neater and quicker.

Coordinating tongue and fingers

Not only do we have to coordinate our fingers, but our tongue needs to match the speed of our finger movements too if we’re to play a genuinely legato melody. Once again, scales can be a useful tool to help achieve this.

Building up speed

Want to play faster? In that case you need to practise the patterns which occur most often in music and gradually learn to negotiate them more quickly. What’s the best way to do this? Yes, you’ve guessed it - scales and arpeggios!

Practising double tonguing

Once you’ve built up some velocity, you might need to explore double tonguing so your articulation can match the speed of your fingers. Again, using simple scale patterns are a great way to work on this without having to think about reading complex music at the same time.

For music exams

Most adult recorder players have no interest in working for exams, but if you’re someone who’s motivated by exams, you’ll need to learn some scales and arpeggios as well as pieces of music. The syllabus for the lower grades may only include a few different keys, but by grade 8 you’ll need to know all the major and minor keys.

Have I convinced you yet?

Assuming I have, you might well be asking some of the following questions…

Do I need to learn all of them?

In an ideal world, knowing all the major and minor scales and arpeggios (plus chromatic and other patterns) is a desirable aim. But this doesn’t mean you have to learn all of them! For anyone even learning a carefully chosen selection is immensely useful.

If you’re not sure where to begin, start by looking at the music you’re currently working on. What key is the piece in? For instance, if you’re playing a sonata with a key signature of two flats, try learning B flat major and G minor - the two scales with the same key signature. The music is likely to work through both of these keys at some point and if you can play these fluently the patterns you encounter in the piece will come more easily too.

Realistically, unless you choose to play Schickhardt’s set of recorder sonatas in every key, most music for our instrument explores a limited range of key signatures. It’s unusual to see recorder music in more than three sharps or flats, so I would recommend aiming for fluency in these keys before you worry about the exotic realms of D flat major or G sharp minor.

Do I have to learn them from memory?

This is a much debated topic among students and teachers. For music exams you’re expected to learn the prescribed scales and arpeggios from memory, but as we’ve already noted, many adult learners have no interest in testing themselves in this way.

In order to play scales fluently from memory you need to be completely on top of the finger patterns, knowing precisely which fingers to move between each note. This requires what is often called ‘muscle memory’, although in reality our muscles don’t have memories. This process is actually achieved by generating strong connections between our brains and the nerve pathways used to send instructions to the fingers. To achieve that (I plan to explore this more in a future blog post) requires lots of repetition, and in my experience, the process of memorising such patterns definitely seems to be harder for some people than others.

Memorising scale and arpeggio patterns presents a particular challenge for players of wind instruments. With the piano or a string instrument, there’s a logical visual pattern as you work your way up and down the keyboard or fingerboard. In contrast, each note on a wind instrument of any type requires a different combination of fingers. Yes, moving between some of these is fairly logical. But I’m sure you’ve noticed how that logic disappears when it comes to cross fingers (particularly flat and sharp notes) or the upper extremities of the recorder!

An additional challenge we face as recorder players is the limited range of our instrument. Most woodwind instruments can play scales covering at least a two, and sometimes three, octave range in all keys. In contrast, the recorder can comfortably manage a handful of scales at two octaves, but for most intermediate level players an octave and a half is the limit. This means scales come in different shapes to maximise the range we cover, either turning at the top or the bottom of the instrument. Remembering which scale follows which pattern is an additional thing to learn and can add extra stress to the process.

For my Score Lines subscribers I created scale sheets showing some of these patterns, which can be downloaded from your Members’ Area. I’ve linked to the treble recorder sheet here, but if you’d like access to all of them please feel free to subscribe here - it’s free and there are lots of other exclusive goodies for you to download besides the scales!

While learning scales and arpeggios from memory is undoubtedly desirable, I would argue that playing them from music is probably just as useful for most amateur recorder players. One of the most important skills to develop is sight reading (I’ve written a blog about this here) and being able to recognise scale patterns and convert them into fluent playing is a great way to achieve this. As with most skills, do this by starting slowly and gradually building up some speed.

How fast should I play them?

As with so many things, it depends! If you’re using a scale to develop your tone you might do best to play it very slowly - perhaps four beats on each note. But if fast playing is your aim you’ll need to take a different approach.

When I first started having lessons with Philip Thorby, I spent about three months solely working on slow scales and other exercises as we focused on developing my tone and legato playing. Ok, this may sound rather extreme, but I was aiming for a career as a professional player so it was absolutely necessary. My technique certainly benefitted from this approach and I finally began to understand scales and arpeggios in a way that set firm foundations for everything I was to learn later. Taking this approach with even just one scale and arpeggio can be hugely beneficial if it helps you focus on the foundations of your technique.

The most important thing is to play your chosen scale or arpeggio correctly from the very beginning. If that means you start out playing each note at a metronome speed of just 60 that’s absolutely fine, as long as the notes are 100% right. When you can consistently play all the notes fluently and cleanly at that speed, gradually increase the tempo until you reach your desired tempo, checking at every point that you’re still maintaining the same consistency and precision. A metronome is a really useful tool here to hold you at one speed.

How often should I practise my scales?

I’m a big advocate of little and often. Having a huge practising splurge on your scales just once a week makes it difficult to achieve consistent results. A much better way is to programme in short, frequent practice times - maybe five or ten minutes every day. This way you remind your fingers of the correct patterns at regular intervals so they become habitual more quickly. Perhaps even keep a recorder out at all times (a plastic instrument can be handy if you prefer to put away your wooden recorders) so you can pick it up and play a scale for a minute or two every time you walk by.

Which variety of minor scale should I practise?

Minor scales come in two different species - harmonic and melodic. Harmonic minors use the same notes whether you’re ascending or descending, so they’re slightly easier to memorise. However, they also include an augmented second interval (the 6th and 7th notes, which sound vaguely reminiscent of a snake charmer’s flute), circled in red below, which is less commonly used in western music.

A Harmonic Minor

In contrast, a melodic minor scale raises the 6th and 7th notes by a semitone on the way up and returns them to their original pitch on the way back down. This is an added complexity to memorise, but these melodic shapes (hence the name) are more frequently found in the music we play. For this reason, if your plan is to practise them with music and you only have time to work on one type of minor scale I’d recommend the melodics as a priority.

A Melodic Minor

Using scales and arpeggios creatively

Most readers of this blog won’t be looking to become professional recorder players, so being able to play in every key with total fluency and at high speed is probably not your aim in life! But you can still use these patterns to improve your playing and have some fun along the way. Here are a few ways you could use them…

Vary your tempo according to your intention

If you want to improve your tone you need to focus on quality rather than speed. For this I would pick an easy scale (perhaps no more than one sharp or flat in the key signature) and play it really slowly. By simplifying the notes you free up your brain to think about breathing deeply and blowing freely, producing the best possible tone on each note. Perhaps spend four slow beats on every note before moving on to the next, breathing as often as you need to, always focusing on using the optimum breath speed for each fingering.

If speed is your motivation, again begin at a modest tempo but focus on keeping your fingering even and well coordinated with your tonguing. Perhaps use a metronome to ensure you maintain a consistent tempo. As you perfect each speed setting, switch up the tempo by a small amount and repeat the exercise several times. If you begin to stumble, take the metronome down by a couple of notches and refine your playing before moving on. Be methodical in your approach and you’ll be surprised how much progress you can make in a fairly short space of time. If you’ve built up a good turn of speed with an easy scale why not take the tempo back down again and try it with a more complex key signature?

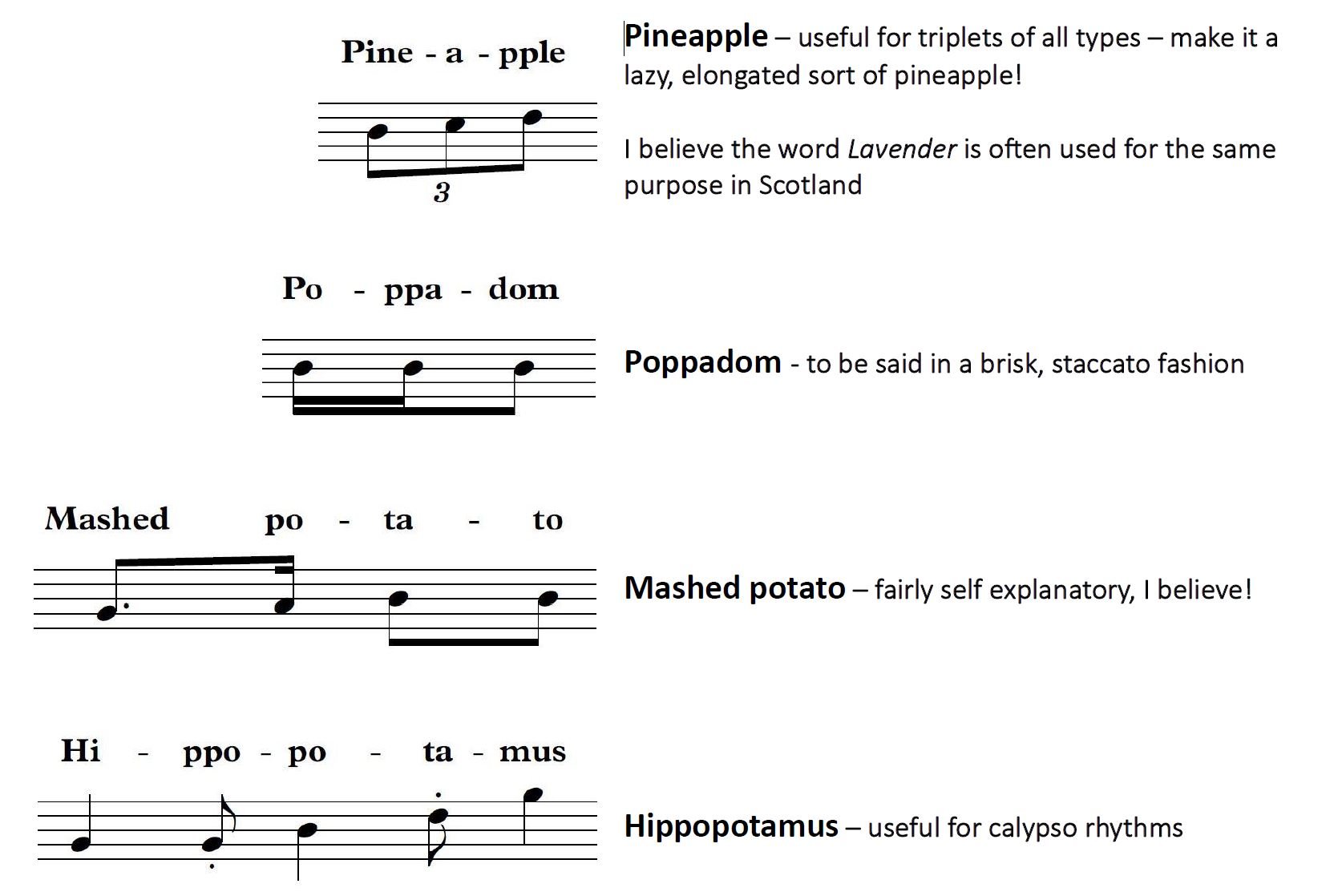

Experiment with different articulation patterns

The music we play often contains a wide variety of articulation, from long tongued passages to intricate patterns, where small groups of notes need to be slurred here and there. It’s a good idea to begin by practising scales and arpeggios smoothly tongued, staccato and in long slurs as these all demand different technical skills.

Alongside these single technique scales I recommend you also practise patterns that require you to mix slurring and tonguing - you can see some of my suggested patterns below. These are the sort of patterns you’ll encounter in the real world and if you can apply them to your scales they’ll seem less scary in context. These are just a few of my ideas, but don’t be afraid to come up with your own variations.

Four varied articulation patterns you could try out

Be playful

There’s no reason why you must always play complete scales. Don’t be afraid to be playful and creative. Breaking a scale down into groups of four or five notes, running up and down, may help you really master the transition between specific fingerings more quickly. Once you’ve got that fluency you can then glue these small groups back together into complete scales. For instance, you could break up the F major scale shown below like this:

Breaking an exercise like this down into bitesize pieces is a recognised technique, called chunking. It’s immensely useful as a means of building up fluency and consistency, allowing our brain to focus more efficiently on small amounts of information.

Explore different note patterns

Bored with just whizzing up and down your scales as printed? Why not add some variety and explore them by playing the notes in a different order? For instance you could play each one in thirds like this…

You could follow the same principle with fourths and fifths too, although these are harder….

If you’ve learnt every key how about mixing them all up together? One of my favourite challenges is to go up one scale, then move up a semitone and come back down the next one - for instance upwards through F major, down via F sharp major, up via G major, down via A flat and so forth. The same exercise is possible with the minor keys too. If you can play both of these fluently you can award yourself a generous gold star!

Major keys

Minor keys

Finally, look for the satisfaction in a scale played really well!

You may not feel the need to learn scales in every key, and for less experienced players such an aim may be too ambitious anyway. However, there’s a satisfaction to be gained from playing even one or two of them really well, even at a slow tempo.

Scales and arpeggios can be a valuable opportunity to find a contemplative zone, focusing on a simple task done to the best of your abilities. I enjoy spending a few minutes at the start of a practice session playing scales really slowly, closing my eyes and listening to my tone. I focus on the quality of my sound, tailoring the speed of my breath and the strength of my articulation to suit each individual note. By doing this I reinforce the good habits I’ve learnt over the years, as well as warming up mind, fingers, tongue and lungs before I move onto more demanding music.

I’d love to hear your thoughts about scales and arpeggios. Are they something you avoid at all costs, or have you cultivated a love for them? Perhaps you’re still on your journey to becoming a zen scale-master? If you have tips you want to share with others or experiences you’ve found useful over the years please do leave a comment below.