How deep do your recorder foundations go? Do you enjoy playing the full range of recorders, or are your eyes still focused on the highest instruments?

Today we’re going to take a look at the bass branch of the recorder family tree. If you already play a bass instrument I hope I’ll have some useful tips to help you improve your skills. And for those who are yet to dip a toe in these deeper waters perhaps I’ll open your eyes to the possibilities and joys of larger recorders.

It’s amazing how the recorder world has expanded its horizons, just within my adult life. When I first attended the Recorder Summer School as a teenage student there were a good number of bass players, but the larger sizes of instrument were still rare - maybe just one or two each of great and contrabass. I was so excited by the sound of these larger recorders in the massed playing sessions I even sent my parents a postcard to tell them all about it!

These days it’s not unusual for us to welcome between 10 and 15 great basses and a similar number of contrabasses to massed playing sessions at the Recorder Summer School. We often have a handful of instruments which are larger still, bringing even greater depth to the music. These wonderfully sonorous instruments offset the potential shrillness of highest recorders, creating a range of tones which would have been unimaginable fifty years ago.

My first foray into the bass recorder world

I first discovered the bass recorder early in my teens. Rummaging in the school music cupboard, I found an old bass recorder with thick orange varnish, a good layer of dust and home to at least one spider. Evidently no one had touched it in years, so I asked my teacher if I could try. She said yes, so I took it home, evicted the spider, washed out the crook and gave it a go. I’d recently begun playing the piano and could read bass clef, so I set about figuring out where the notes lay on the recorder.

We’d been working on James Carey’s Mock Baroque with the school recorder ensemble and presence of the bass meant we now had a full consort and no need for the optional piano part. That made me indispensable and I was hooked!

Several years later, at my first Recorder Summer School I included a PS on that postcard I sent my parents, nonchalantly adding, “Please can I borrow some money to buy a bass recorder”! Cheeky, perhaps, but I did already have the money saved up at home and I couldn’t wait to play an instrument of my own with those rich low notes - far better than the wheezy old school bass!

Why play the bass recorder?

Put simply, bass really is beautiful!

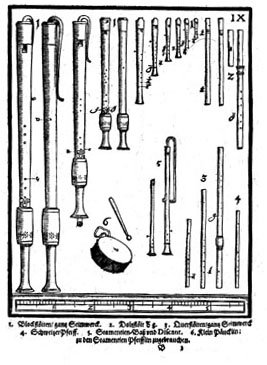

Renaissance bass recorders, where you blow directly into the windway.

The mellow tone of the bass (sometimes also called a basset) is just gorgeous and you’ll find a warm welcome in any recorder ensemble. There’s a great deal of pleasure to be derived from playing the bass line in consort music - you’re helping create the foundations upon which the rest of the music is built. In some music (especially Baroque) you form the musical powerhouse, while in polyphonic music (for example Renaissance consorts) you play an equal role in the interplay between voices. Yes, there are some pieces where the basses draw the short straw and have less to do, but in general composers today understand the need to write interesting parts for everyone - not just the high voices.

If you really want to enjoy the gorgeous tones of the lower recorders it’s becoming more popular to offer eight foot ensemble options at many courses and playing days. This is a group where the highest line is the tenor recorder, with multiple parts extending down to the contrabass and sometimes beyond. Playing the bass recorder in one of these allows you to enjoy these mellow tones from the centre of the ensemble, really feeling you’re part of the action. I conduct such a recorder orchestra (you can learn more about METRO here) and I regularly welcome between 40 and 50 people to our playing days to luxuriate in the lush tones.

The benefits of playing the bass recorder

All recorder players understand the need to work on breath control and tone production. The bass can be a tremendously useful tool here because it makes greater demands on our lungs. Filling the larger bore of the bass with air requires you to breathe more deeply and efficiently to produce a good tone. Even if you can’t manage to play long phrases, the very act of practising the bass recorder will improve the way you use your natural lung capacity, meaning you’ll be able to play further on one breath on the smaller instruments too.

Another benefit of playing the bass is the way it opens up your awareness of other elements of recorder technique. Let’s think about some of these bass specific tips, but remember they’ll help your technique on smaller recorders too.

Top tips for bass players

Breathing and tone

Finding enough air is a challenge for everyone who plays larger recorders. You might assume you need to blow really hard to fill the larger bore of the bass, but you’d be wrong. Yes, a bass will swallow up all the air you can throw at it, but if you overdo things and blow too harshly your tone will be coarse and forced. The principles are just the same as any other size of recorder - make a full, rounded tone, but don’t force things. If breath control and tone production is something you know you need help with, do take a look at the blog I wrote about just this here.

You will run out of air!

Unless you’re superhuman you’ll find your lungs run dry more often when playing the bass recorder. Just how soon this happens will depend on your natural lung capacity, and you may need to accept that full four bar phrases just aren’t possible, at least at first.

To combat this, get creative and find more places to breathe. In passages with lots of detached notes you’ll probably be able to take small top ups between notes. In more sustained music it may be necessary to make room to breathe. Use this as an opportunity to reconsider your phrasing.

Whatever you do, you mustn’t compromise your tone or tuning. So often I hear long notes which sag towards the end, losing tone quality and pitch. This simply isn’t acceptable or pleasant to hear. Instead, find somewhere extra to breathe so you can support your tone to the end of every phrase.

If you find yourself playing in an ensemble with several players per part there are other strategies at your disposal. I often ask ensembles to, “make it sound like you’re playing a four bar phrase”. Note the language I used there. I’m not asking them to play four bars without a breath, but instead to give the aural impression they’re doing that. Bass playing is often a team effort. Have a chat with your neighbour and agree where each of you will breathe. Perhaps one could breathe in at the most musical places, while the other takes breaths in really daft, unmusical spots. This way there will be at least one person playing at all times and you will give the impression that you’re collectively playing the full phrase! Talk to any contrabass player and you’ll find they do this all the time.

No chiffing please!

If there’s one thing that’ll spoil an elegant melodic bass line it’s an ugly ‘chiffing’ sound at the start of each note. Bigger sizes of recorder are particularly prone to this - a by-product of the instrument’s larger windway. If you’re not sure what I’m talking about, grab your bass recorder and play some notes with really strong tonguing. Close your eyes and really listen. Do you hear a percussive sound at the beginning of each note? That’s what I mean by chiffing.

As with the breath, it’s easy to assume a bigger recorder needs stronger tonguing. In reality, because bass recorders are so prone to this effect, you need the opposite - gentle tonguing. For high notes this may seem counterintuitive, but as long as your breath is moving quickly enough, even the highest notes don’t need anything more than a gentle tongue stroke.

Yes, there may be pieces where this percussive effect is required or even desirable, but in 99% of cases you should aim to avoid chiffing.

Fragile low notes

All recorders suffer from the same challenges at their extremities. Bass recorder music rarely ventures up to extreme high notes (that’s not really the point of the instrument), but being able to play the lowest notes cleanly and clearly is vital. Gentle tonguing and slower moving air will mostly help you achieve this, but stretching your fingers to the lowest notes can be challenging, especially if you have smaller hands. I wrote about the challenges of extreme low and high notes recently so do check this out if you haven’t already seen it.

Before you begin playing, take a moment to check your bottom joint is in exactly the right position. Scan through the music and see whether you need bottom F or F sharp most often. If you only need one of those notes, why not position the footjoint so you can reach that key most comfortably. If you play one of the square Paetzold bass (or larger) recorders do check your instrument’s joints are firmly pushed together too. Even a minor leak at one of the joints can stop your bass notes singing clearly.

Flexible fingering

As you venture lower in the recorder family you’ll find a need to be more flexible with your fingerings. Standard fingerings, which work so well on higher instruments, may not always be in tune on a bass. For instance, low E flat is often out of tune when played with the standard 0/1-34 fingering. If your instrument came with a fingering chart, check what it recommends for E flat. Many suggest using finger 5 rather than the usual finger 4 on the right hand. It may take a while to adjust to this change but you’ll find it easier to play in tune with others.

Spend some time playing slow scales on your instrument and get to know its foibles. A tuning meter can be useful here as a way of checking which notes are particularly sharp or flat. If you have a smartphone there are several free tuning meter apps available to download. Don’t be afraid to refer to your instrument’s fingering chart to check what the manufacturer recommends. To get used to these different fingerings, find easy tunes and scales you can play to build up the muscle memory.

A handy alternative fingering for top C sharp.

One notable quirk of many bass recorders is a difficulty with top C sharp. Most plastic bass recorders simply won’t play the note with the standard fingering unless you’re able to slur up or down to it. You won’t need this particular note very often, but it pays to be ready when you do. Happily, there’s an alternative fingering which works really well on almost all basses - see the diagram here:

As you can see from the chart, this fingering is a little out of the ordinary, but you’ll be grateful you learnt it when you suddenly need a top C sharp!

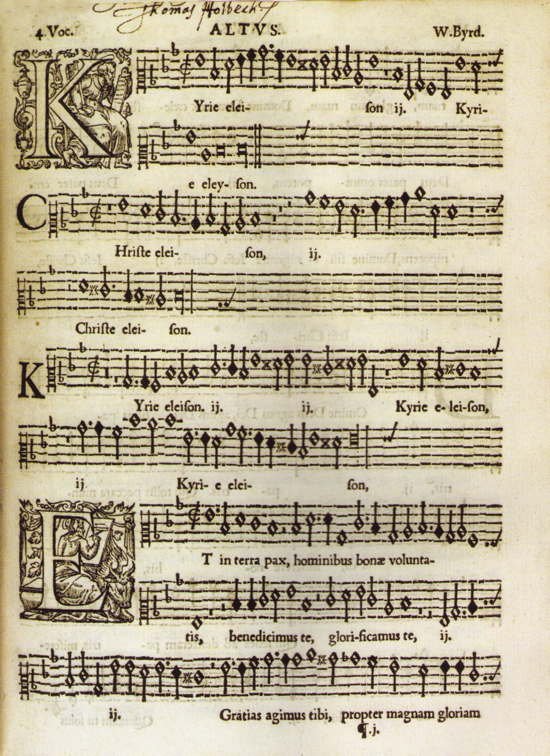

A word on clefs

The most common clef for bass recorder music is the bass clef. That seems logical, doesn’t it? Well, yes and no! Bass recorder music is notated with the lowest note appearing just beneath the bottom line of the stave. Look closer though and you’ll see a small 8 just above the clef - that means every note sounds an octave higher than written.

If you were to rewrite the same music at sounding pitch in the treble clef you’d find the lowest note is just five notes beneath Middle C! Compared to a cello, bassoon or tuba (all of which can play notes at least an octave an a half lower still) that barely counts as a bass instrument at all.

Of course notating the music in bass clef makes it easy to read because you’ll encounter relatively few leger lines. For this reason alone it’s worth getting really comfortable with the bass clef. Try to read the notes for what they are rather than relating the pitches back to the treble clef and doing a form of transposition. Not only does it make reading quicker but it also means you’ll always know the name of the note you’re playing at any time.

Although the bass clef is most commonly used for the bass recorder, it can be useful to practise playing it from the treble clef too. Occasionally you’ll find bass recorder parts printed in treble clef and being able to play treble recorder music on the bass can be handy if, for instance, you spontaneously want to try a piece of Renaissance music out an octave lower with an ensemble. This sort of mental flexibility is always worth cultivating, much as it sometimes pays to be able to read treble recorder music an octave higher.

Advice for new bass players

If you fancy having a go on the bass recorder but haven’t yet taken the plunge, the prospect can seem a little daunting. To help you take those first steps here are my thoughts on how you might get started.

Which type of bass recorder?

Unlike the small recorders you probably began with, basses come in many different forms. This can be bewildering at first, so let’s take a look at the options.

Straight or Knick?

Look at images of historic instruments and they all tend to be straight. Renaissance basses are generally designed so the player blows directly into the instrument. This offers the benefit of a clear, full tone because your breath has a clear path through the windway to the labium. The disadvantage of this design is you do need quite long arms to reach the fingerholes!

One solution to the long arm problem is to add a crook - a curved pipe which leads to the headjoint, shortening the distance from mouthpiece to fingerholes. Larger renaissance recorders (great basses and lower) used this design and most 18th century bass recorders did too. While this may be more comfortable, the narrowness of the crook can make the sound a little less direct. You may also need to anticipate the beginning of notes as the breath has further to travel before it reaches the labium. That said, some players prefer an instrument with a crook so it’s very much a matter of personal preference.

A new innovation over the last thirty years has been the knick bass. This is fundamentally a straight recorder with an obtuse angle built into the headjoint. You retain the ability to blow directly into the windway, but this bend brings the main body of the recorder closer to you, so pretty well anyone can play one. In recent years this type of bass recorder has become by far the most popular, simply because it offers a great balance between tone and comfort.

Basses by IKEA?

Herbert Paetzold with his family of square recorders.

Another twentieth century innovation has been the development of square basses. They’re quite a common sight on recorder courses these days, but I’ve often heard non-recorder players ask if they were purchased from IKEA! These instruments were first developed by Herbert Paetzold in the 1950s on the principle that if you could have a square wooden organ pipe that sounded like a recorder, surely it must be possible to make a square, wooden recorder. Initially they were made from marine plywood (water resistant and cheaper than exotic hardwoods) but today you can also buy 3D printed models made from a material called Resona. The first of these square recorders were the larger great and contrabass variety, but more recently they’ve become available in bass (and even tenor) sizes too.

Plastic or wood?

This choice may come down to budget. Relatively inexpensive plastic knick instruments are a great way to begin exploring the world of the bass recorder. These begin at around the £200 mark for a Triebert (the Early Music Shop’s own brand model) and increase to £325 for a Yamaha.

If you want to venture into wood prices begin at around £1000 so you’ll probably need to be sure you’re going to stick with the bass before taking the plunge. And that brings me onto another consideration…

How many keys?

For larger recorders to be played comfortably keywork is needed. At its simplest this may just be a single key for the right hand little finger so you can reach bottom F. However, for many people having just one key may makes some of the holes impossible to cover. Most knick basses have at least one extra key for both the left and right hands - a feature which makes the bass playable for pretty well anyone. Many basses require a smaller hand stretch than a tenor recorder.

For this reason alone, a plastic knick instrument is a great place to start your bass recorder career. They produce a good tone, offer a comfortable playing position and are relatively inexpensive compared to wooden or square models. If you already play in an ensemble ask around and you may even find someone who’s upgraded to a wooden instrument and might be willing to loan you their plastic bass to try.

When it comes to wooden recorders, I really would advise you to find a shop where you can try some instruments. This way you can learn which shape recorders suit you best and understand which ones have keywork that fits your hand shape. If you don’t live near a recorder shop (and sadly few of us do) it’s worth looking out for recorder courses and summer schools as many of them host pop up recorder shops on site.

Getting comfortable

If you’ve figured out which type of bass recorder fits you best you must also consider how to support your instrument. All basses tend to come with a sling supplied and this may be all you require. It hooks onto the back of the instrument so you can suspend the recorder from your body. Most people hang the sling around their neck, but don’t overlook the option of lengthening the strap to stretch it from one shoulder across your body instead. This reduces the strain on your neck and may be more comfortable for long periods of playing.

Another option I sometimes use when sitting is to cross my legs at the ankle. I then rest the bell of my recorder between the bottom of my calves. This takes any strain away from the neck and means the body of the recorder is vertical between my knees. Of course this won’t work if you’re wearing a short or fitted skirt, but it’s a handy solution when wearing trousers!

A bass recorder spike

If you like this idea but don’t find resting the bass on your ankles comfortable, a third solution is to use a spike. These attach to the bottom of your instrument and you adjust the length of the spike to rest it on the floor. The ground takes all the weight and you can play your bass vertically between your knees or to one side if you prefer. Some wooden basses now come supplied with a screw-in spike (the Kung Superio model, for instance) but you can also buy after-market ones which attach via an adhesive Velcro ring stuck to the bottom of your recorder. This is perhaps the most comfortable way to play, but if you like to stand up the spike is unlikely to be long enough unless you rest the end of it on a stool or chair.

Bring your bass to you

My final piece of advice with regards to playing position is as important as your choice of support.

I often see players stretching their chin forward to reach their bass recorder. This puts a tremendous strain on your neck and can cause injury over long periods. The key thing here is to find a playing position which is comfortable and then bring the bass to you. This may be as simple as shortening your sling or moving the bottom of your spike a little closer to your body. Don’t forget too that most knick basses have two points of adjustment in the headjoint. A slight tweak to one or both of them may mean you don’t need to strain or bend your neck awkwardly. The best solution is to sit in front of a mirror and see how your posture looks. If it looks uncomfortable it’ll almost certainly feel uncomfortable after a long playing session!

Don’t forget to consider the height of your seat too. This is particularly pertinent with great and contrabass recorders as they’re often less adjustable than a regular bass. Look around any recorder orchestra and you’ll see many of the contra players bring their own seats or stools to ensure they’re at just the right playing height. Sometimes a couple of chairs can be stacked together to increase your height, but take care as this can also make you less stable.

Books to get your started

Over the years many books devoted to the bass recorder have been published, with several designed for complete beginners. These are the ones I’ve found useful to help my pupils get started over the years….

Denis Bloodworth - The Bass Recorder Handbook (Novello)

The original bass recorder tutor book and still handy today. The music increases in difficulty quite quickly, but it’s packed with helpful information about fingerings so I think it’s still a great addition to any bass player’s library.

Rosemary McGillivray - Mrs McGillivray’s Welcome (Hawthorns Music TT01)

A bass recorder tutor book with a Scottish flavour. Rosemary brought together lots of lovely tunes to get anyone started on the bass recorder. The book begins with a fingering chart, an introduction to the bass clef and some helpful advice, followed by lots of carefully graded tunes to play, many of which share Rosemary’s Scottish heritage. Each time a new fingering is introduced there are plenty of melodies to help you put it into practice. Very well thought out and my top recommendation for new bass players.

Hugh Gorton - Recorder Practice Books 16-23: Grades 1 to 8 (Recorder Music Direct)

A series of graded books, each packed with tunes to get you practising the bass recorder. Each book contains hundreds of melodies, providing you with almost endless repertoire to build your confidence and technique.

Playing the bass with others

One of the main reasons to play the bass recorder is to make music with others as part of an ensemble or orchestra. Playing any new size of recorder with others for the first time can be daunting, but don’t let that put you off. A good place to begin is in the some of the easier ensemble sessions at recorder courses, or at a massed playing session at larger recorder events. You’ll find safety in numbers, meaning you can play as much or as little of the music as you’re able to at first without fear of standing out.

Of course, if you don’t want the pressure of playing with others face to face straight away, don’t forget there are lots of easier consort pieces and video recordings over on my own Consort Downloads page. These give you the chance to make mistakes without feeling you’re holding anyone else up and you can repeat them as often as you wish! Look for anything that’s marked *Easier* as your starting point.

Heading deeper still…

Let’s assume you’ve taken the plunge with the bass recorder and you’re enjoying its rich tones and the chance to be part of the music’s engine room. What’s next?

How about one of the bigger basses?

It’s worth taking a moment to talk about the naming practices for big basses as this isn’t always consistent. You’ll notice among my consorts I use the terms great bass and contrabass. These are the names most commonly used here in Britain, but there are other systems too. As the range of bigger basses gradually expands the British system runs out of options. Below the contrabass we have the subcontrabass (sounding an octave below the great bass) - all logical so far. But when you reach the next member of the family (an octave below the contrabass) you run out of names - should that be the sub-subcontra?

In Europe and the US a different system has been adopted where the contrabass and lower have names which usually relate their size to the smaller types of bass. This is entirely logical, but not consistently used in Britain yet. The clearest way of explaining this is perhaps illustrated by the table below, showing the two naming systems, along with an explanation of their relative pitch. The two largest sizes are still relatively unusual, but they’re gradually increasing in popularity.

The keys of a Paetzold conrabass recorder

Many recorder ensembles now have a great and/or a contrabass player among their number. If you’ve heard them in action you’ll understand how powerful these instruments can be. Of course I don’t mean powerful in terms of loudness, as they’re relatively quiet compared to a tuba! However, even a single great or contra can add to the impact a recorder consort simply through its depth. The best comparison I can make is sound difference when an organ has a pedals - doubling the bass line alone somehow seems to increase the gravitas of the regular bass notes. This is why I was so blown away by that massed playing session at the tender age of 16, even when there were just a couple of contras among a massed group of 140 recorders.

Now buying a great bass or contrabass is an expensive business, so it’s not something you’ll necessarily want to leap into straight away. However, players of big basses are often generous souls and are sometimes willing to allow others to try their instruments if they see the potential to win more folk over to the deep end of the orchestra.

Even if you can’t try an instrument out for yourself, grab every opportunity to sit near the big basses when playing in an ensemble. Just playing the bass among the big boys will give you an aural glimpse of their wonderfully lush tones. I should warn you though, once you’ve dipped your toe into the deep, warm big-bass waters you’ll be spoilt for life - it’s addictive! I personally love playing the great bass in larger ensembles because you’re part of the bass team, but can also find yourself in the enveloped in the midst of the harmonies.

* * *

After our exploration of all things bass, have I tempted you to dip your toe into these deeper waters? Or maybe I’ve made you think about ways you could improve your bass playing?

Either way, I hope you’ve found some useful advice among my words and I’ll leave you with the Berlin Recorder Orchestra playing the Albinoni Adagio almost entirely on low instruments. Turn up the volume and luxuriate for eight minutes in the sound from their forest of big basses!