The guidance of a conductor can be immensely helpful, but how often do you really think about what the person standing in front of you is trying to convey through their gestures? I work with many ensembles and orchestras of differing standards and know only too well how my movements can make or break a performance. Of course, if the musicians I’m directing don’t understand my gestures I might as well be standing there waving semaphore flags!

In this week’s blog I share with you some of the secrets of the conducting world to help you get the best from the next conductor you work with.

Image created by Chenspec

Do all conductors do the same thing?

Up to a point, yes. However, it’s important to understand that not all groups of musicians have the same needs. An ensemble of inexperienced players will probably most value a clear beat to help them keep in time. But a professional orchestra is entirely capable to playing a vast array of repertoire without needing someone to keep them in line. For them, a conductor is the person who shapes the music to their own artistic vision. A regular beat is largely unnecessary, so instead they use different gestures to indicate their musical wishes. For instance take this performance from Mozart’s 40th Symphony by Sir Simon Rattle and the Berlin Philharmonic. He barely gives the beat, instead showing the direction and shape of the music in his gestures and facial expressions.

In my working life I adapt to suit the musicians I’m conducting at any moment in time. I’m very happy to be a musical coat hanger, on which inexperienced musicians hang their beats. Equally, it’s a joy to be freed of the need to beat time and to be able to offer gestures which show my musical intent.

When I first started conducting it was a relief if I could keep a regular beat, starting and stopping people successfully. Changes of tempo were scary because I had to know in advance how I would communicate them clearly. I often made mistakes. To anyone among my readers who saw some of my early, error strewn, efforts, I can only offer my apologies! Over time I gained confidence and was able to add other gestures to my repertoire, sharing more information. I now understand that if the musicians I’m directing don’t do my bidding it’s almost certainly because of a flaw in my communication skills, rather than in their playing. It’s a sobering thought and one that means I’m perpetually on a mission to improve.

How did I learn to conduct?

If you’ve ever felt even the slightest inclination to try conducting yourself you may be interested to hear the route I’ve taken to this point. I never expected to find myself here, and I like to think I’m proof that you don’t need to be a Simon Rattle to be a useful conductor. The path I’ve followed is open to anyone - if you fancy having a go you can start with baby steps and learn as you go. Amateur recorder groups often find themselves in need of a conductor and they’re mostly very understanding towards those who are brave enough to get up and have a go.

My earliest experience of conducting was through the ear tests which were part of my music grade exams at school. The requirements have changed a lot over the last three decades, but in my time one of the tests required the candidate to conduct along with a piece of music played by the examiner. This revealed whether you could determine the time signature of the music and certainly wasn’t designed to reveal future directors of the Berlin Philharmonic! Here I learnt how to beat 2, 3 and 4 time and it helped me better understand what the conductor of our school band was doing too.

During my music college years I had choral conducting lessons with a lovely chap called Stephen Jackson, who was director of the BBC Symphony Chorus for many years. I learnt a lot in theory but found the prospect of conducting my peers utterly terrifying. Stephen once told me I looked ‘scared witless’ as I attempted to direct part of Brahms’ German Requiem! In my last year as a student I was trusted to conduct an arrangement of my own with the recorder ensemble from the college’s junior department. This was a less scary prospect and with some encouraging advice from the ensemble’s tutor I began to enjoy the experience.

From there I gradually began working with groups on courses and conducting is now a major part of my working life. If you’d told me this would happen back in those choral conducting classes I’d have roared with laughter!

Learning is all about watching and stealing!

Aside from those terrifying conducting classes at college, I freely admit most of my conducting education has come from watching other conductors in action. At concerts I’m perpetually observing the gestures they use, noting which ones have the desired effect and which don’t. My conducting technique has shamelessly been stolen from conductors of recorder groups, orchestras, brass bands and choirs!

Even watching bad conductors can be educational. I find myself noting things that don’t work, or places where the musicians are playing well in spite of the conductor. A few years ago I recall watching a brass band competing in a contest in Yeovil. They gave a creditable performance, in spite of their director who conducted the entire piece at a forte dynamic. The band ignored this, playing quietly when required despite his misleading gestures.

Learn the language of conducting

Now you know a little more about my route into the world of conducting, let’s take a look at some of the things I do to help the musicians I coach. Remember, while there are some universal gestures, others are unique to individuals. The information I share with you here is my take on conducting. Next time you’re in a rehearsal take some time to observe what your conductor does. You may pick up some useful tips which are helpful for your playing and any conducting aspirations you may have!

To use a baton or go freehand

This is a very individual one. Orchestral conductors tend to use batons, while choral directors more often employ more flexible hand gestures. I tried a baton in my earlier years but always felt I had more flexibility and control without. The important thing is clarity and it’s entirely possible to be unclear with either method!

Right or left handed

Occasionally you’ll encounter a conductor who uses their left hand to impart the beat rather than the right. In fact, many years ago I conducted left handed for a while because of tendinitis in my right shoulder and I’m not sure anyone even noticed! Does it matter? Not at all. Most people aren’t distracted by a left handed beat, but do remember that the beating patterns will be a mirror image of those made by a right handed conductor.

Deciphering the patterns

One topic on which conductors tend to agree is beating patterns. In the following video I explain the most common patterns. I also cover some tips about the quality of the beats I give.

If you struggle to spend time watching the niceties of the various patterns while playing, there are two crucial landmarks to look out for - upbeats and downbeats. The first beat of any bar will go downwards, while the final beat (whether there are 2, 4 or 7 of them) will always go upwards. If you ensure you’re always on the first beat of your bar as the conductor’s hand descends you’ll immediately stand a better chance of being on the the right beat elsewhere in the bar!

Follow my leader

As Sir Thomas Beecham once facetiously said, “There are two golden rules for an orchestra: start together and finish together. The public doesn't give a damn what goes on in between.” OK, this is a gross oversimplification, but the way we start and finish music does matter.

As I show in the next clip, there are different ways to begin a piece of music. With less experienced groups I may conduct a whole bar to set them up with the tempo, while for more advanced musicians a single upbeat might be sufficient. As you’ll see, the quality of these introductory beats is very important to ensure a clean start.

Once I’ve got an ensemble going, another important part of my job is to ensure the various parts come in at the right time. No matter how good you are at counting bars rest, it’s reassuring to see a gesture from the conductor to confirm you’re coming back in at the right time. This won’t always be an extravagant gesture - sometimes even a moment of eye contact is enough. The important thing is for me to inspire confidence in my players, so I always try my hardest to be there in their hour of greatest need. That said, as a player, don’t always rely on your conductor to bring you in - your key entry may coincide with a moment when your conductor is fighting a fire elsewhere, managing another part which has gone off the rails!

Sometimes less is more

Over the years I’ve come to appreciate how powerful a conductor’s gestures can be. Perhaps an accent will be absent because I didn’t show it in my beat. Or maybe I’ll give an extraneous gesture which results in notes played where they shouldn’t be.

The example I always give to groups when explaining this idea is the following clip from a Christmas episode of Mr Bean. Rowan Atkinson may not be a professional conductor, but the responses of the brass quartet to Mr Bean’s movements are so well observed - and so funny too!

The following is an example from a piece I conducted just last week. The accompanying voices play chords, but irregularly on just one or two beats per bar. Initially I gave every beat equally and this resulted in notes being played in the rests. When I changed my approach, making more meaningful gestures (sometimes reinforced by the left hand) on just the beats where chords are written the result was more successful.

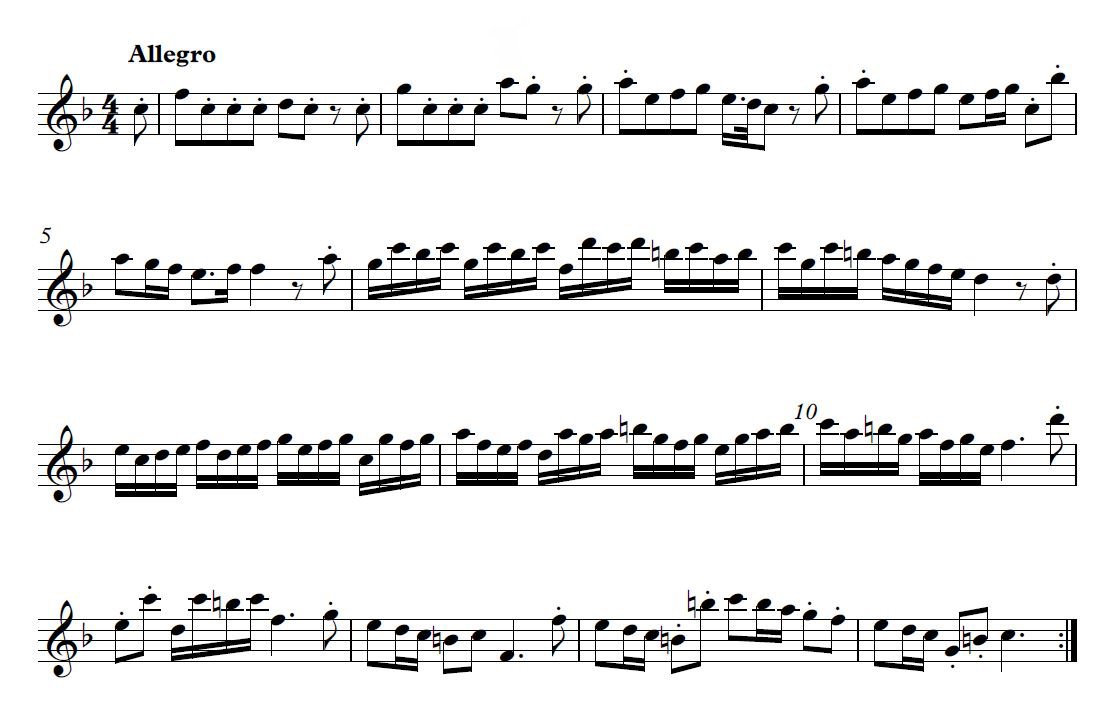

Below you’ll see the section I’m playing above, taken from Steve Marshall’s Variations on A Chantar. You can see the irregular accompaniment, with chords occurring in a different place in each bar.

Variations on A Chantar by Steve Marshall

Conveying meaning in music

As well as showing the beat in my conducting, I’ll try to convey other information about the music, such as dynamics, articulation and phrasing, through my gestures, as I show in the following clip.

Preparation is key

If you read my blog post four weeks ago you’ll already know I’m a big fan of annotating music with a pencil. That’s especially true when I’m conducting, particularly if I’m to help others play to the best of their abilities. Score preparation is a personal thing, but for those of you who may find yourself one day conducting an ensemble it may be helpful to have a glimpse into my methods.

There are no hard and fast rules for marking up scores and my markings will depend entirely on the type of music and its level of complexity. But here are some of the things I frequently mark into my own music:

To start with I’ll circle things which need my immediate attention, such as speed changes and I’ll figure out how I’m going to handle pauses. Sometimes (as in the example below) I may note a particular rhythm or melody which will help remind me of the tempo I’m aiming for.

I’ll often write large numbers in above the score to flag up where the time signature changes. A conductor who’s beating the wrong number of beats per bar is as much use as a chocolate teapot!

Labelling entries with instrument names so I can give helpful leads. If several parts come in simultaneously I’ll often group them with a square bracket.

I’ll look out for accidentals I think players might miss. I’ve become good at predicting these over the years - after a while you gain a sixth sense about which ones will be forgotten. Of course, marking these in my score doesn’t make the musicians more likely to play them, but it does remind me to listen out for them!

Writing in larger bar numbers. This is an age related thing - larger numbers mean I can refer to sections quickly in rehearsal without perpetually whipping my glasses on and off!

Notes about articulation, dynamics, phrasing, interesting harmonies and more. Often there creative decisions I need to make, to put my own stamp on the way the music is played, introducing light and shade.

In a fugal piece I will often mark each entry of the theme so I can see its journey through the score.

Below you’ll see a page from Steve Marshall’s The Dream-Country, which I’m currently rehearsing with one of my orchestras. You’ll see a lot of the items mentioned above and I’ll almost certainly add more notes as we build up our interpretation of the music for performance.

Building trust between conductor and musicians

When I stand in front of an ensemble, especially in concert, I’m very aware of my responsibility to assuage any nerves, helping the musicians play to the best of their abilities. At a basic level this means I need to be utterly consistent, maintaining the beat clearly and giving leads where the players have come to expect them. Naturally, I am only human and I do make mistakes occasionally, but I try to keep them to a minimum.

For me a big part of building trust is being in eye contact as much as possible. As a player, feeling the conductor actively involved in the performance and seeing the whites of their eyes is comforting - you feel you’re in this together and the support is mutual. When people are nervous, a little eye contact and a smile go a long way!

Of course eye contact works both ways. It’s a great myth that conductors are powerful - we have as much power as you give us! I can express my musical ideas clearly through my gestures, but if the players don’t watch, my efforts will be worthless. When the interaction becomes genuinely equal the results can be truly awe inspiring.

Some years ago I conducted a recorder orchestra piece in a concert at the end of a week’s course. We’d rehearsed thoroughly so I felt confident we’d give a good performance. Things started well and we successfully negotiated the tricky corners - a combination of concentration and interaction to get everyone through their exposed and awkwardly timed entries. Then we came to the big solo moment for one of the players, which had been rock solid all week. Imagine my terror as the soloist came in half a bar early! I had a split second decision to make - bring the orchestra back in at their allotted time and hope the soloist would realise, or to just jump two beats and hope the entire orchestra would realise we’d lost half a bar. I plumped for the latter option and to my immense relief they came with me - one of those occasions when they watched like hawks and understood my gestures correctly. From there we sailed through to the end and enjoyed a huge adrenaline rush of relief as the audience applauded! The orchestra could have assumed I’d make a mistake and stuck to their guns, but the trust we’d built paid off and we lived to tell the tale.

~ ~ ~

So there are some of my thoughts on the weird and wonderful world of conducting - hopefully you’ll have found at least one helpful nugget of information within. When you consider the concept, it’s a strange job. We stand in front of a group of musicians, waft our arms around, apparently in control of proceedings, then take all the applause when the performance is over. I hope my words help you understand it’s not all about the glory. I never take for granted the trust musicians place in me and any rehearsal or performance is the ultimate example of teamwork. Without you I wouldn’t have a job and it’s an honour to forge that sense of trust every time I conduct.

If you’ve ever had so much as a passing thought about trying this yourself please don’t hesitate to try, even if it’s just a case of gathering four friends to play some simple tunes while you beat time. Seeing the music from both sides of the fence can be simultaneously terrifying and immensely rewarding and even if you never try it a second time you’ll learn a lot. If you have experience of conducting why not share some of your tips in the comments below, or you could tell us about your finest and/or scariest moments in rehearsal or performance. Or if you prefer to remain safely ensconced in the orchestra, why not share some of the tips you’ve picked up from conductors you’ve worked with - there’s always something new to learn.