Hotteterre’s iconic image of a recorder player’s hands from his treatise, Principes de la flute traversiere, de la Flute a Bec, et du Haut-bois, Op.1

When you consider the myriad of things we concentrate on while playing the recorder it’s a miracle we make music at all, isn’t it? You’ve got breathing, tone production, articulation and fingering to consider and that’s without even making any decisions about the finer musical details.

Multitasking is a skill all humans struggle with - our brains just aren’t designed for focusing on multiple tasks at once. The way we overcome this in music is to practise certain skills to the point where they become instinctive and habitual. Once this happens, that habitual element of playing can continue while our brain focuses more heavily on other things. I see the challenges of multitasking all the time in the musicians I work with. A pupil can be playing with a gorgeous, rounded tone, but when faced with a sudden flurry of fast notes, or a passage in a tricky key, their tone suddenly suffers because they’re now busy thinking about their fingers.

This short video clearly explains the phenomenon of how we manage (or fail to manage!) multitasking.

To develop good technique to the point where it becomes habitual it’s important to separate out the various elements, focusing on just one skill for a period. In previous posts I’ve talked about breathing, tone production and legato playing, so today we’re going to focus on moving our fingers well.

Be a tortoise rather than a hare

My aim today is to get you thinking about the quality of your finger movements rather than the speed of them. You remember the old adage, “Don’t run before you can walk” - that applies to recorder playing too!

None of the techniques and exercises I’m going to share here need to be done at speed immediately - that can come later. Instead, take your time, focusing on efficiency rather than whizziness. In a further blog post we’ll discuss how to acquire speedy fingers - to do that as well today would almost certainly require too much multitasking!

If you practise the techniques below and turn them into good habits you’ll be in a much stronger place to develop speed in the future.

How do you hold your recorder?

I often see people doing battle with their recorders, holding them in curious ways - this inevitably has a detrimental effect on finger efficiency. Let’s go back to basics for a moment - I explain exactly where to begin in this short video:

Comfort with larger recorders

A welcome innovation over the last twenty to thirty years has been an increase in the number of knick recorders available. These are larger instruments (tenor downwards) which incorporate a bend in the headjoint, often some additional keywork. Such modifications are so helpful as they bring the body of the recorder closer to the player, reducing the stretch required for the fingers and arms. Straight tenor recorders often provide the greatest challenge for those with smaller hands. I know many players who now enjoy playing the tenor recorder because a knick and some extra keys have brought the fingerholes into comfortable reach for them.

Knick instruments have one drawback though - the bend in the headjoint changes the angle of the recorder’s centre joint. As I explained in my video, a straight recorder sits upon your right thumb in an almost horizontal position. This allows gravity to help pin the recorder against your thumb, adding stability. With a knick instrument, the centre joint takes an almost vertical position, so gravity then becomes a negative force, trying to pull your recorder to the ground! There are several possible solutions here, the simplest of which is to use a thumb rest. Tucking your thumb beneath a thumb rest gives the recorder a point of balance and the force of gravity holds it there. But with heavy recorders, or for those with arthritic thumbs, this can of be painful so there are other solutions you can try.

Attaching a sling or neck strap to the back of your recorder allows you to hang the weight of the instrument from your neck or shoulders, perhaps in combination with a thumbrest. If this isn’t comfortable, a third option is available for the bass recorder - to rest the bottom of the instrument somewhere. I often do this by crossing my ankles, resting the bottom of the recorder between my calves. If this isn’t comfortable you can also buy adjustable spikes which allow you to rest the instrument on the floor. I often use the latter solution with my bass and I love the way it takes all the strain away from my fingers.

Ultimately, if your body is comfortable while playing, this frees up your fingers to move efficiently, making your playing more fluent. It’s definitely worth spending some time finding the right solution for you.

The human hand - a flawed design

Evolution is an amazing thing, slowly making adjustments and improvements to the design of our bodies over many, many generations. However, from a musician’s perspective, there are still a few things which could be improved. One of these is the design of our hands.

It’s a common misconception that our fingers are controlled by muscles within our hands. In reality, the movement of our fingers is created by the muscles in our forearms. These muscles connect to tendons, which run through our wrists and hands into our fingers. As the forearm muscles flex they pull on the tendons, creating the finger movements needed to play the recorder.

It’s within these tendons you find a small flaw. A single tendon runs through each finger and into your wrist. However, the tendons from your third and fourth fingers fuse together in the centre of your hand before continuing as one single tendon into your wrist. The fact that these two fingers share a tendon means they work better as a team than they do individually. This is why your third and fourth fingers don’t work as independently as the others. This is particularly critical when we play forked fingerings, such as E flat on the treble recorder or B flat on the descant. These notes require the third and fourth fingers to work independently of each other – something they don’t do easily.

I’d love to think that if enough of us continue playing musical instruments of any type, eventually evolution will sort this design flaw out. Hopefully in a couple of million years time recorder players won’t face the same difficulties as we do with forked fingerings!

Keep reading and I have some exercises later which will help you make these weaker fingers work more efficiently.

Good vibrations

Do you have a recorder close by? If so, pick it up now and play a few notes. Focus on the sensations you feel through your fingers.

Do you feel gentle vibrations through the pads of your fingers? Or is your sole sensation that of the wood or plastic beneath your fingertips? This exercise will help you understand whether you’re covering the holes in the right way. Use the minimum amount of pressure and you can feel the vibration of the air column beneath your fingers. If you can’t feel this vibration you’re pressing your fingers down with too much force, and working harder than you need to. Being aware of this will help you to better understand whether you are working your fingers efficiently.

Remember too that you should always cover the holes with the pads of your finger, not the tips. This gives you maximum sensitivity and the best chance of sealing them effectively.

Active versus passive

An efficient finger technique is vital if you ever wish to play at speed. You should aim to use just enough effort to open and close the finger holes. Use too light a touch can result in air leaks, while pressing too hard with your fingers expends more energy than necessary.

A useful way to achieve the perfect balance of finger pressure is to think in terms of active and passive movements. Bringing your fingers down to cover the holes uses gravity as an assistant and is a passive movement. In contrast, when lifting fingers up, you’re working against gravity so this movement has to be an active one. Play a few notes on your recorder, perhaps a short scale, and really focus on these two types of movement. Harnessing, the power of gravity will help you cover the finger holes with ease, while the greatest amount of energy is always used when lifting the fingers.

Don’t work too hard!

When it comes to finger movements I always tell my pupils to be as lazy as they can get away with. Of course, I don’t mean taking a slapdash, “that’ll do“ sort of attitude. Instead, think in terms of expending the minimum energy necessary to get the most efficient result.

Are you a recorder player whose fingers are a model of efficiency and neatness? Or maybe you’re someone whose digits flap like flags in the wind?! It’s simple common sense that if you keep your fingers close to the recorder they’ll travel more quickly than if you lift them high. However, common sense doesn’t necessarily have a huge amount to do with what we actually do with our fingers!

If you’re a finger flapper, spend some time playing a simple piece of music, where you have the spare mental capacity to be able to focus on your finger movements, without being distracted by other elements of technique. Playing in front of a mirror can be really helpful here, because it’s often easier to see which fingers are moving too much when viewed from the perspective of an another person.

Another mental image I suggest to my students is to imagine a mini electric fence placed horizontally two or three centimetres above your fingers. If you’re familiar with Star Trek, I’m thinking of a miniaturised version of the electronic force fields they use to close off parts of the Starship Enterprise. With this imaginary force field in place, think what would happen if you lifted your fingers too high and they came into contact with it. A quick zap of electricity would certainly focus the mind, deterring you from lifting your fingers further than they need to travel - not that I’m suggesting you should actually electrify your recorder!

If you’d like to see efficient fingering in action I recommend watching this video of a young Frans Bruggen performing the Vivaldi Concerto in C, RV441. He looks so utterly relaxed and his fingers lift just enough to clear the holes, but no more. For those of who don’t speak Dutch, the music begins at around two minutes.

Snappy mover

If you’re playing a slow piece of music, do you think your fingers should move quickly or slowly?

I often pose this question to students and you’d be surprised how many people get the answer wrong. Your fingers do, of course, need to move quickly and snappily, regardless of the tempo of the music. When you’re playing a slow, singing line the notes change at a leisurely pace and the spaces between the notes are minimised to create that legato effect. Move your fingers too slowly and the transitions become blurred and glissando-like. I often compare this to the voices of The Clangers in the 1970s TV cartoon! To avoid this always move your fingers quickly and efficiently to create a singing melody with crisp transitions between notes.

Putting everything into practice

Having considered basic principles, it’s now time to put this into practice.

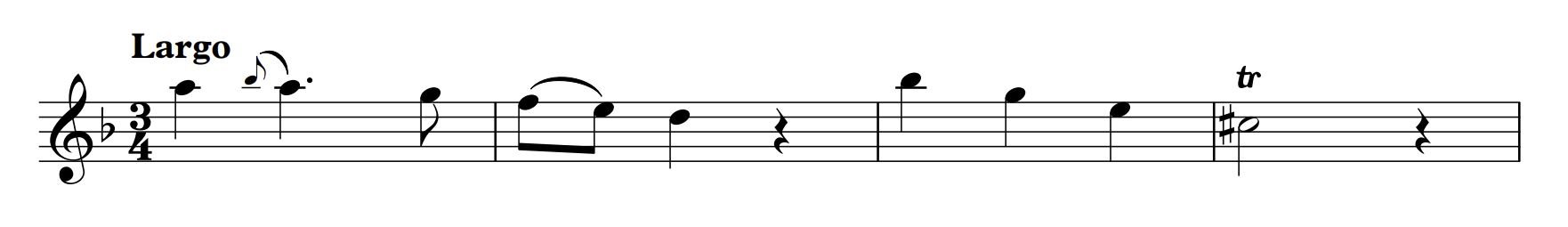

As I mentioned earlier, trying to do too many things at once will almost certainly end in failure. Your best bet is to choose something simple, allowing you to focus entirely on your finger movements. Perhaps the simplest exercise is a five note scale like the ones shown below - one for the fingers on the left hand, one for the right.

Begin very slowly, but make sure every single finger movement is quick, neat and as minimalist as possible. Remember, the further, your fingers move away from the recorder, the longer they take to come back down again. The time saved by making small movements is important whether you’re playing a slow melody or virtuosic concerto. Even better, play these passages with every note slurred. Slurring leaves nowhere for your fingers to hide – every little inconsistencies in their movement will be audible. Slurring also exposes unevenness in tone and rhythm so don’t forget to listen out for those too!

As you begin to improve the quality of your finger movements, gradually increase the speed of these short exercises. As the tempo builds, take care not to slip back into bad habits, with fingers flapping wildly.

Training badly behaved fingers

When we looked at the anatomy of our hands earlier, I mentioned how the connected finger tendons make forked fingerings harder to play neatly. This is because such notes require movement of two or more fingers together, frequently including one of your weaker fingers. The ultimate challenge comes when a note change requires you to move fingers up and down simultaneously, using digits on both hands.

The exercise below demands all these things between notes 2, 3 and 4. Try playing it now (ideally slurred) and listen to the neatness (or not!) of your finger movements.

Now play the same exercise while standing in front of a mirror. Really study the way your fingers are moving.

If you hear blips between notes this is because one or more fingers are moving out of sync with the others. Watching this process in a mirror (seeing them from the perspective of your recorder teacher, for instance) makes it much easier to spot which finger is slower than the others. If you find it hard to spot the badly behaved finger, concentrate on any which are moving upwards. Remember, lifting a finger requires you to work against gravity, requiring fractionally more effort. You’ll almost certainly find misbehaving digit is a lifted finger, moving just a fraction slower than the others.

Having located the recalcitrant digit, next time, really focus on that particular finger, trying to make it work just a little bit harder than the others. Over time you’ll probably noticed a pattern. Third fingers are the most common offenders, simply because they’re weaker as a result of the shared tendon. There’s nothing you can do to change the way your hand is built, but by concentrating on the way your fingers move, you can gradually encourage them to move more efficiently.

Once you can do this neatly while playing slowly, then begin to increase the speed, bit by bit, always ensuring your finger movements are neat and precise before moving the tempo up another notch.

Do you have your own tips for dealing with lazy fingers?

I’m sure there will be things I’ve mentioned today which chime with you. We’ve all wrestled with difficult passages and berated our fingers for creating all sorts of blips and imperfections. If you can recognise these bad habits while practising, you’re in a good position to gradually improve upon them. Maybe you have your own exercises and techniques for improving finger control? If you do, why not leave a comment below and share some of them with us – there’s always room to learn from each other.

The tips and exercises I’ve shared today are ones that work for me, but we all tackle things in our own unique way. I’d love to hear some of your tips and tricks!